Key Considerations

- Python is ideal for prototypes, but Java excels at scale with strong concurrency and enterprise integration.

- Use Gradle for setup, Jsoup for static pages, Selenium for dynamic sites, and WebMagic for big crawls.

- Our Hacker News demo configures Gradle, rotates proxies to scrape blog posts, and saves the results to CSV.

While Python often gets the spotlight for web scraping, there are times when Java is the better fit. If your project already runs on a Java framework or needs to plug directly into enterprise systems, staying in Java can save you time and complexity.

In this tutorial, we’ll build a Java scraper from scratch using reliable libraries. You’ll see how to send HTTP requests, parse HTML with CSS selectors, and extract data efficiently. Step by step, we’ll walk through the full process so you can put Java to work for real-world scraping tasks.

Why use Java for web scraping

If you’ve read our tutorials on building a Python web scraper for scraping Amazon or Best Buy, you know the code might be long, but it still runs with a single command.

Java doesn’t work that way because the language forces structure. Each public class has to live in its own .java file. You’ll end up with a main file to run the whole thing, then separate files for your scraping libraries, scraper configuration, and maybe your HTTP client too.

It’s a different process that takes more setup. So why do people still perform Java web scraping when Python is so much easier?

Strengths of Java for web scraping

The core strength of Java in web scraping comes from how well it supports enterprise-grade systems. Unlike ad-hoc scripts meant to scrape data once or twice, Java is designed for environments where compliance, auditability, and system integration are mandatory.

Performance and security

When you’re scraping 100 pages, Python gets the job done. But at 100,000 pages with near real-time requirements, the Global Interpreter Lock (GIL) in CPython can become a bottleneck.

The GIL prevents true parallelism for CPU-bound tasks. To push past it, developers use multiprocessing or async I/O, but each adds complexity in memory, coordination, or setup.

This is where Java shows its strength.

Java threads run as native OS threads, so tasks can execute in parallel across CPU cores without GIL restrictions. Combined with thread pools, executors, or high-performance frameworks like Akka or Vert.x, Java gives you concurrency that scales naturally for heavy workloads.

Java virtual machine (JVM) ecosystem & libraries

The modern web scraping tool needs more than a basic request and response. Today’s process often involves:

- Launch a headless browser to render dynamic, JavaScript-heavy sites

- Maintain sessions and cookies so the scraper behaves like a logged-in user

- Handle CAPTCHAs and bot defenses with third-party solvers or human-in-the-loop services

- Process HTML content using libraries that support CSS selectors or XPath

- Pull data from PDFs or images with tools like Apache PDFBox or Tesseract OCR

- Stream results into storage

Java’s ecosystem is uniquely positioned to support all of this.

Execute JavaScript, support detection evasion

Selenium WebDriver (Java), Playwright for Java

Real OS threads via ExecutorService, strong typing across browser interactions

Persist login, rotate identities, detect soft blocks

OkHttp + CookieJar, Apache HttpClient + CookieStore, Selenium cookie management

Define session state as a typed object, persist easily to disk or DB, swap logic with ChallengeStrategy interface

Parse pages, work with APIs, extract from PDFs/images

Jsoup (HTML + CSS selectors), Jackson (JSON), JAXP, Jackson XML, JOOX (XML), PDFBox, iText (PDF), Tess4J, ImageIO (OCR/Image formats)

Stream-friendly parsing with GC control, back-pressure support for massive scraping jobs

Push to DBs, pipe to Kafka, batch to cloud or data lakes

JDBC + HikariCP, jOOQ, MyBatis, Kafka client, Pulsar client, AWS SDK, GCS SDK, Hadoop FS

Stable, production-grade connectors, fine-grained transaction handling under load

Use modern syntax, add scripting layers

Kotlin (less boilerplate), Scala (Akka for concurrency), Groovy (scripting/templates)

Mix and match with Java without leaving the JVM, use the right tool for the job while keeping shared memory, types, and deployment in sync

Type safety & maintainability

Java may feel rigid compared to Python when you’re just getting started. But that structure is exactly what pays off later. In Python, you can write a scraper that runs fine until the site changes a small detail, say, a price field switching from 19.99 to 19,99.

Python won’t warn you - the script keeps running, and the error only shows up deep in your workflow. In Java, you have to define data types up front.

If a price can’t be parsed into the declared type, Java will throw a clear exception right at the boundary instead of silently letting bad data slip through. This type safety prevents a whole category of hidden bugs and makes debugging more predictable as your scraper grows in complexity.

Enterprise-grade integration

Java fits naturally into enterprise IT environments. Many large organizations already rely on Java-based middleware, Kafka for stream processing, and Oracle or PostgreSQL for data storage.

When you perform Java web scraping in this context, you can use existing enterprise connectors directly without relying on ad-hoc scripts or wrappers.

Your web scraper runs natively in the existing ecosystem, using the same deployment pipeline, monitoring tools, and security policies as other production services.

This seamless integration is one of the reasons Java web scraping is sometimes used in large-scale ETL workflows. A well-structured scraper built with Java web scraping libraries can pull data from target websites, process HTML content, and push results.

Weaknesses compared to Python

Java brings strong integration, concurrency, and type safety to web scraping, but it isn’t without limits. Compared to Python, the same structure that makes Java reliable at scale can feel like friction when you’re just experimenting.

- Language-level weaknesses in Java

Java is like the friend who spends 20 minutes quoting the rulebook before touching the ball. In scraping, that means boilerplate: setting up clients, builder patterns, type declarations, and try-with-resources, all before you extract a single line of text.

- Ecosystem gaps and friction

Many Java scraping libraries were designed with enterprise networking in mind, not scraping workflows. Python’s ecosystem, by contrast, was shaped by communities that spend their time pulling data from the web, handling blocks, and iterating fast. That’s why frameworks like Scrapy, Requests, and Playwright feel tailored to scraping in ways most Java tools do not.

Python vs. Java for web scraping: Quick guide

Fast, minimal setup

Slower, more boilerplate

Handles broken markup well (Beautiful Soup)

Strict parsing, struggles with malformed HTML

Strong Playwright/Selenium ecosystem

Fewer wrappers, thinner docs

Scales well with async frameworks, but is limited by GIL for CPU-heavy tasks

Strong for parallel jobs with native threads and JVM performance

Relies on external connectors for databases/ETL

Deep integration with Kafka, databases, and JVM-based data tools

Flexible but loose typing

Strong typing, safer at scale

Scraping-first tools & docs

Enterprise-first libraries

Setting up your environment

Time to get hands-on with Java web scraping. First, make sure Java and the other prerequisite tools are installed.

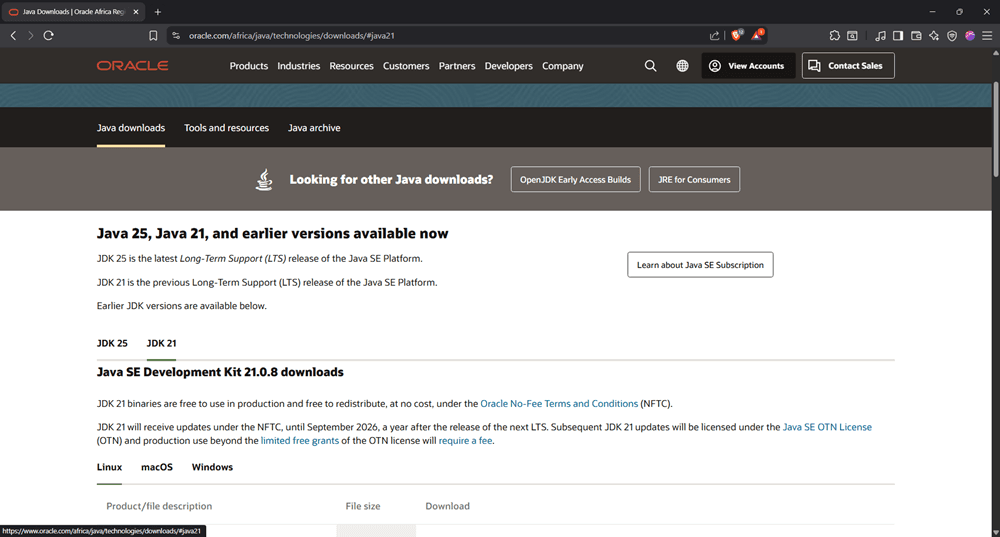

Installing Java on your device

Step 1: Download the Java SE Development Kit (JDK)

Go to the Oracle website (or an OpenJDK provider) and download Java 21, which is the latest long-term support (LTS) version fully supported by Gradle. Don’t grab the newest release beyond 21 just yet. We’ll explain why later.

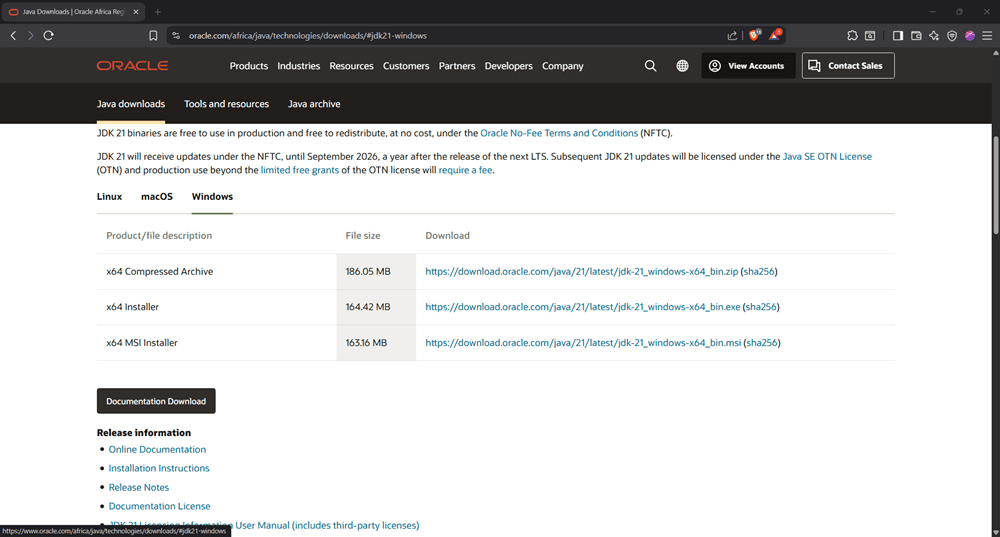

Step 2: Choose your OS and download the JDK package

Select your operating system and download the installer package. On Windows, that’s typically a .zip (or .msi if you prefer an installer). On Linux and macOS, you’ll usually see a .tar.gz. For this tutorial, we’ll demonstrate using the Windows .zip distribution.

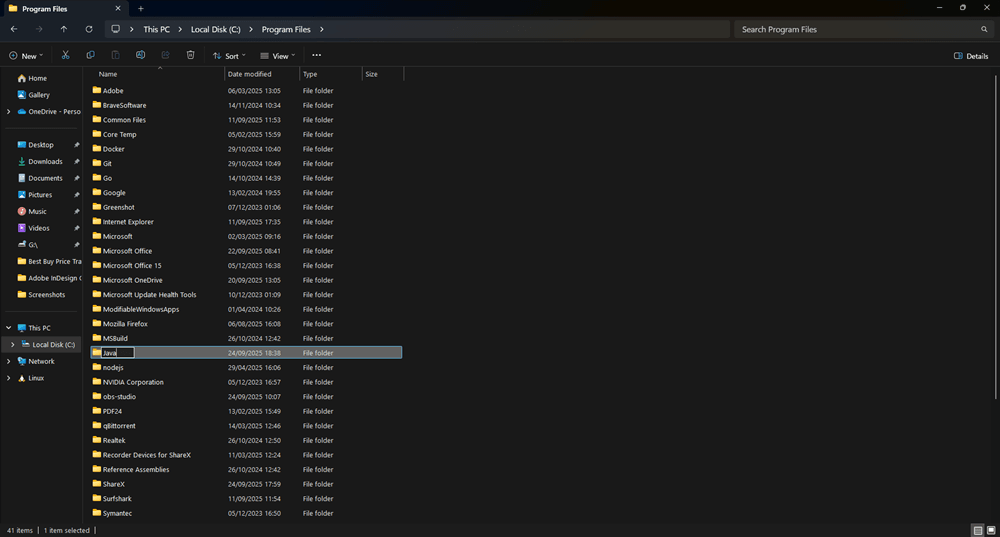

Step 3: Create a Java folder in Program Files

Inside C:\Program Files, create a new folder named Java. This will be the location where you extract the JDK. If you’re using the .msi installer, this folder may already exist, but if you’re installing from the .zip file, you’ll need to create it manually.

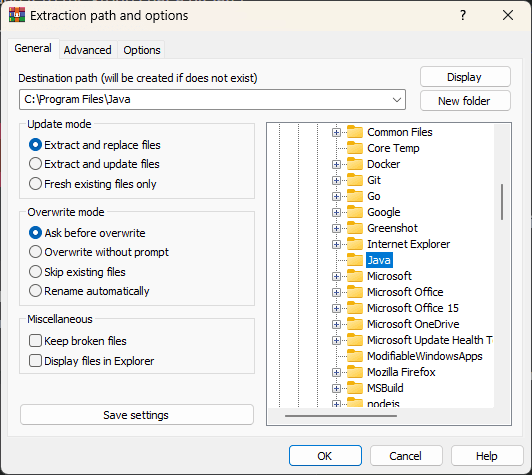

Step 4: Extract the JDK archive into the Java folder

Unzip the downloaded JDK package into C:\Program Files\Java. After extraction, you should see a folder like jdk-21 inside C:\Program Files\Java. This will be the base directory for your Java installation.

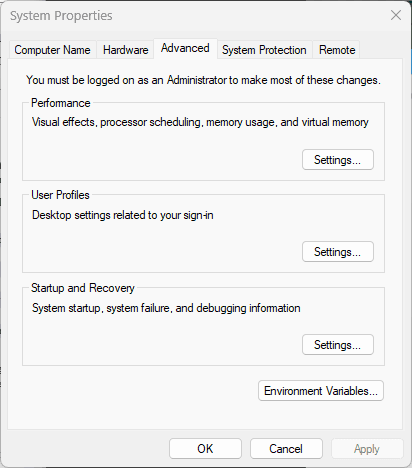

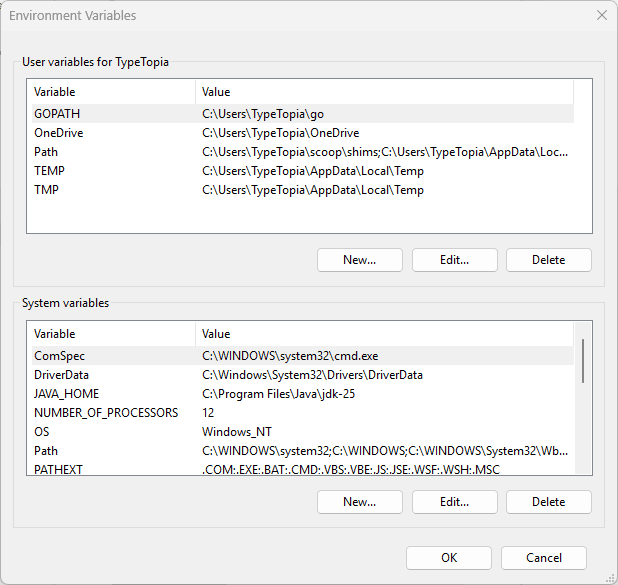

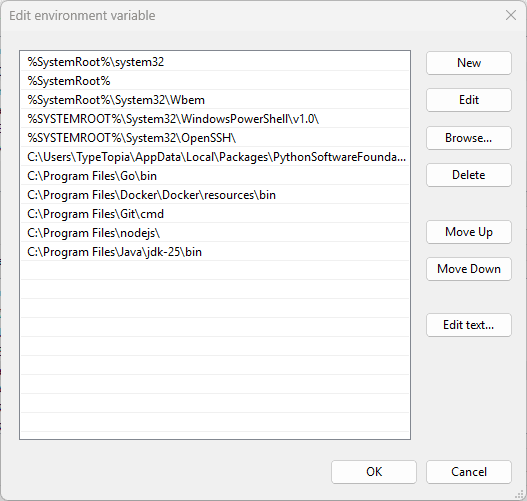

Step 5: Set environment variables

Press Win + S and search for 'Environment Variables'.

Under 'System Variables', click 'New' and enter:

- Variable name: JAVA_HOME

- Variable value: C:\Program Files\Java\jdk-21

Still under 'System Variables', find 'Path', click 'Edit', then 'New', and add:

C:\Program Files\Java\jdk-21\bin

Click 'OK' to save all changes.

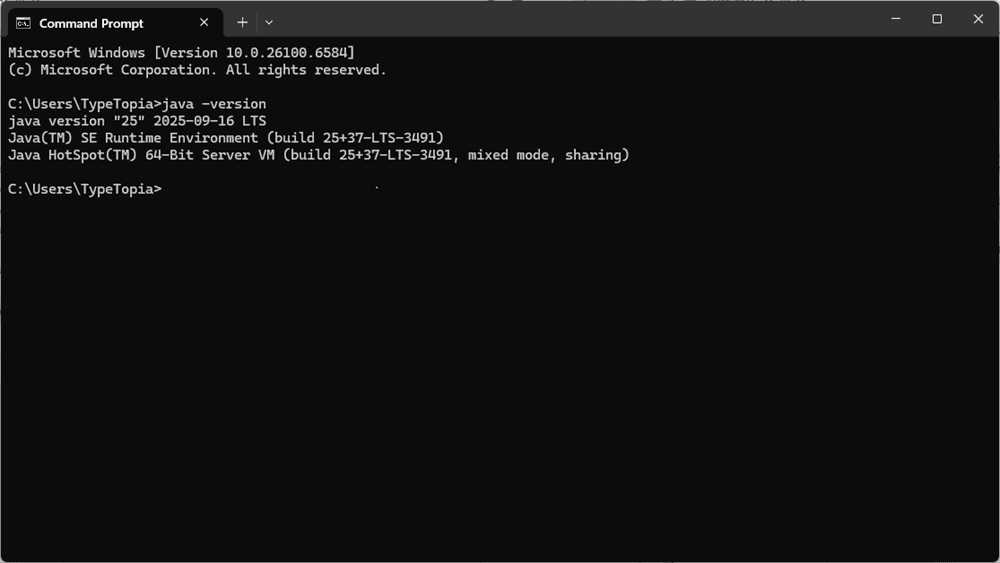

Step 6: Verify installation

Open Command Prompt and run:

java -version

You should see details about your Java installation.

Also run:

javac -version

If both commands return version info, you're all set.

Build tools

If you’re coming from Python, get ready. Java won’t just let you hack away in a single script. In Python, you can install a library with pip, import it, and start scraping in minutes. In Java, even a basic scraper requires more structure.

- Your .java files must be compiled into .class files

- Your external libraries (like Jsoup, OkHttp, or Selenium) need to be declared and resolved

- Your project has to follow the folder and package conventions the compiler expects

You could manage this manually, but it gets messy fast. That’s why build tools like Maven and Gradle are the norm for real-world Java scraping projects.

Maven

Maven gives your scraper a defined structure, handles your dependencies, and takes care of the repetitive build steps behind the scenes. With Maven, you can:

- Manage dependencies like Jsoup, OkHttp, and Selenium without downloading .jar files manually

- Build your project with a single command

- Package your code into a runnable .jar or deployable artifact

- Define your project’s lifecycle so the entire web scraping process - from compiling code to generating output - is repeatable and consistent

To do this, Maven enforces a standard project layout that every Java web scraper follows. It looks like this:

├── pom.xml

└── src/

└── main/

└── java/

└── com/

└── orina/

└── scraper/

├── Main.java

└── HtmlParser.java

└── test/

└── java/

└── com/

└── orina/

└── scraper/

└── MainTest.java

- src/main/java holds the actual logic for scraping web pages, making HTTP requests, and reading HTML content using CSS selectors

- src/test/java contains test files (optional, but valuable when you’re building scrapers that need to run at scale)

- pom.xml is the core of it all. This file defines what Maven should do: what scraping libraries your project needs, which Java version to use, and how to build and run your code.

Gradle

The other tool you can use to manage your Java projects is Gradle, the more flexible and developer-friendly cousin of Maven. It performs the same core tasks:

- Managing scraping libraries like Jsoup, Selenium, and OkHttp

- Compiling your .java files into .class files

- Packaging your web scraper into a runnable .jar

- Defining a predictable build process for your scraper

The difference is how it does those things. Gradle doesn't use XML like Maven. Instead, it uses a more concise scripting language, Kotlin or Groovy, that reads more like real code and gives you room to customize the web scraping process. It’s easier to modify, easier to automate, and more comfortable to maintain when your scraper evolves.

Here’s how you’d tell Maven to add Jsoup version 1.15.3 to your scraper:

<project>

<modelVersion>4.0.0</modelVersion>

<groupId>com.orina</groupId>

<artifactId>web-scraper</artifactId>

<version>1.0</version>

<dependencies>

<dependency>

<groupId>org.jsoup</groupId>

<artifactId>jsoup</artifactId>

<version>1.15.3</version>

</dependency>

</dependencies>

</project>

It works, but it’s long, and everything must be nested in tags. Now here’s the same instruction written with Gradle:

plugins {

id 'java'

}

group = 'com.orina'

version = '1.0'

repositories {

mavenCentral()

}

dependencies {

implementation 'org.jsoup:jsoup:1.15.3'

}

Same result. Jsoup is added to your project. But with Gradle, the code is shorter and more readable. We’ll be using Gradle for this tutorial. Here is how to install it:

Installing Gradle

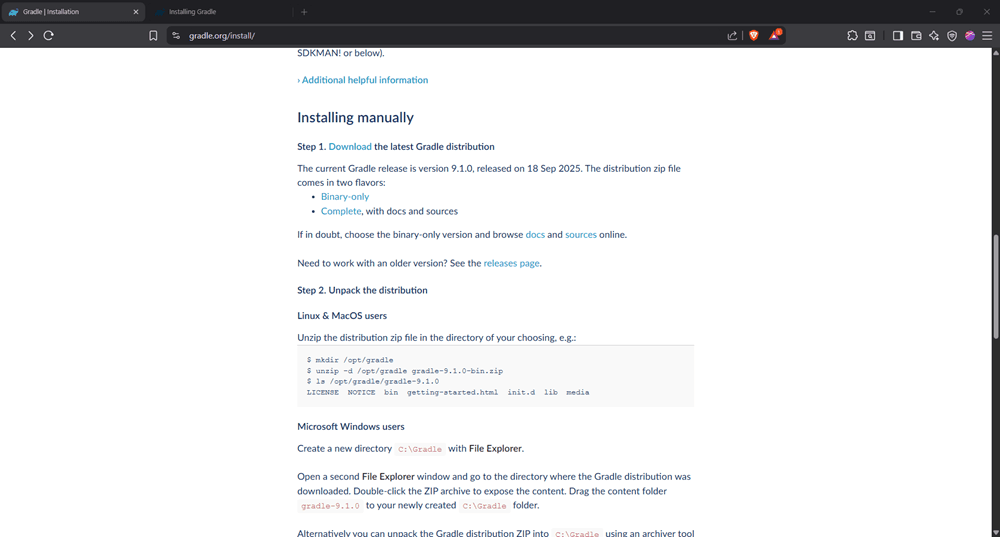

Step 1: Open the Gradle website

Go to the official Gradle website, click the 'Install Gradle 9.1.0' button, and scroll until you see 'Installing manually':

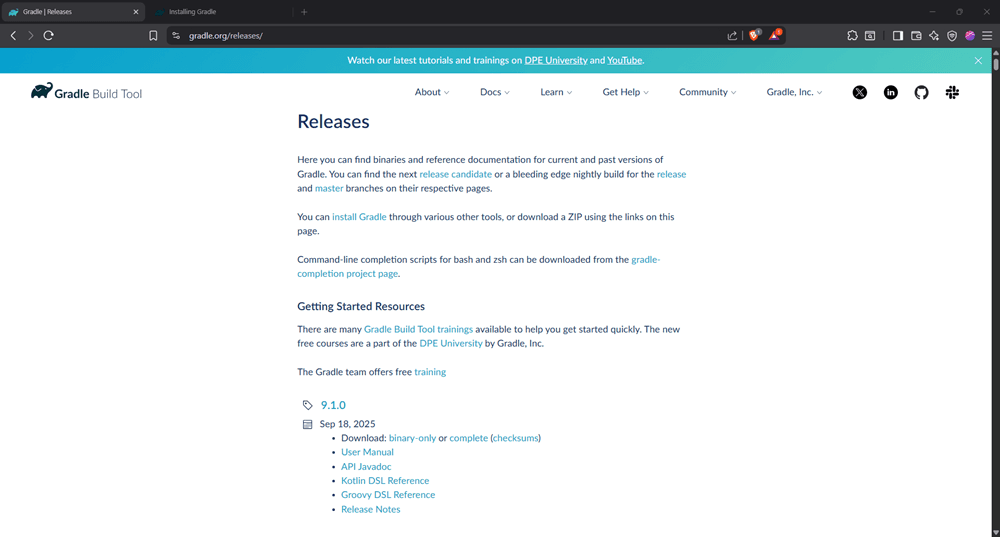

Step 2: Download the distribution

Click the 'Download' button in the first step. You will be redirected to a new page.

Download the complete file.

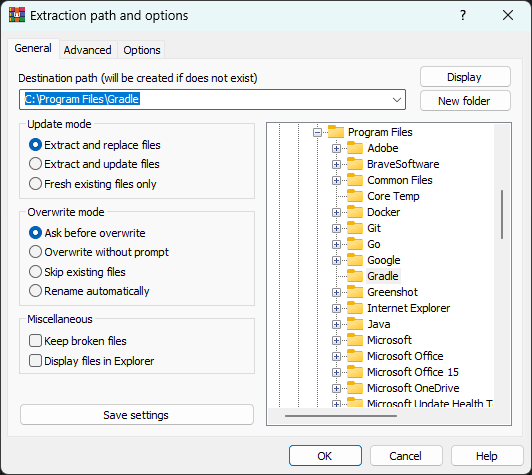

Step 3: Create a Gradle folder

Create the following folder:

C:\Program Files\Gradle

Step 4: Extract Gradle

Extract the downloaded file into the folder above.

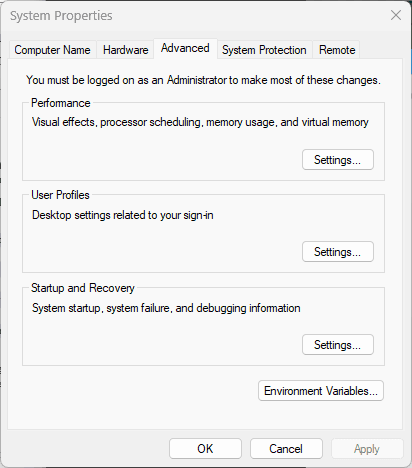

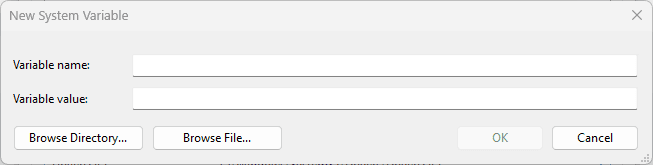

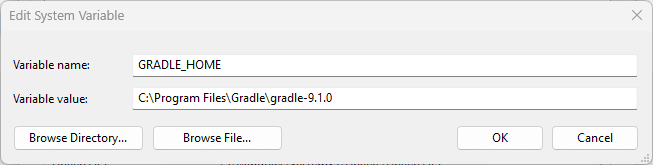

Step 5: Set environment variables

Press Win + S and search for 'Environment Variables'.

You will be redirected to the following window:

Under system variables, click 'New'.

And add:

- Variable name: GRADLE_HOME

- Variable value: C:\Program Files\Gradle\gradle-9.1

Click 'OK' to save.

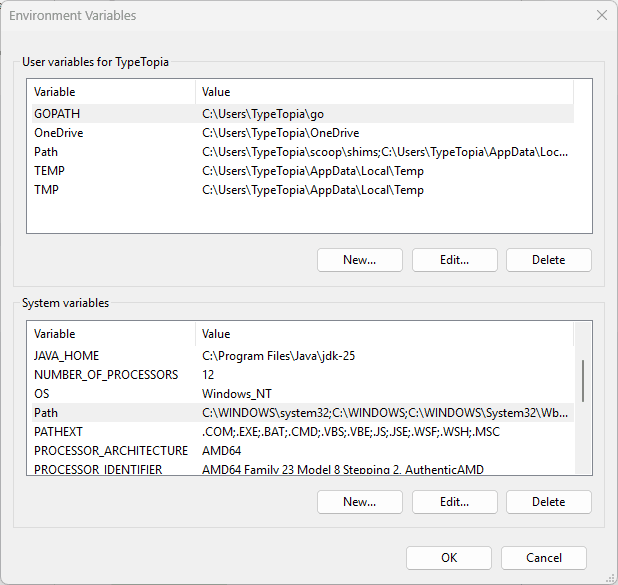

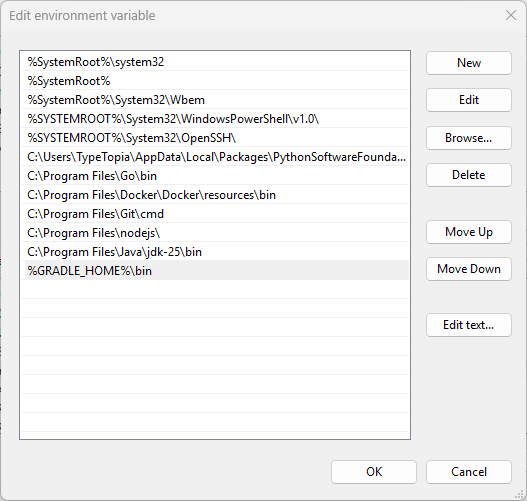

Step 6: Update Path

Select the 'Path variable' in 'System variables'

Click 'Edit', then 'New'.

Add:

%GRADLE_HOME%\bin

Click 'OK' on all windows to save changes.

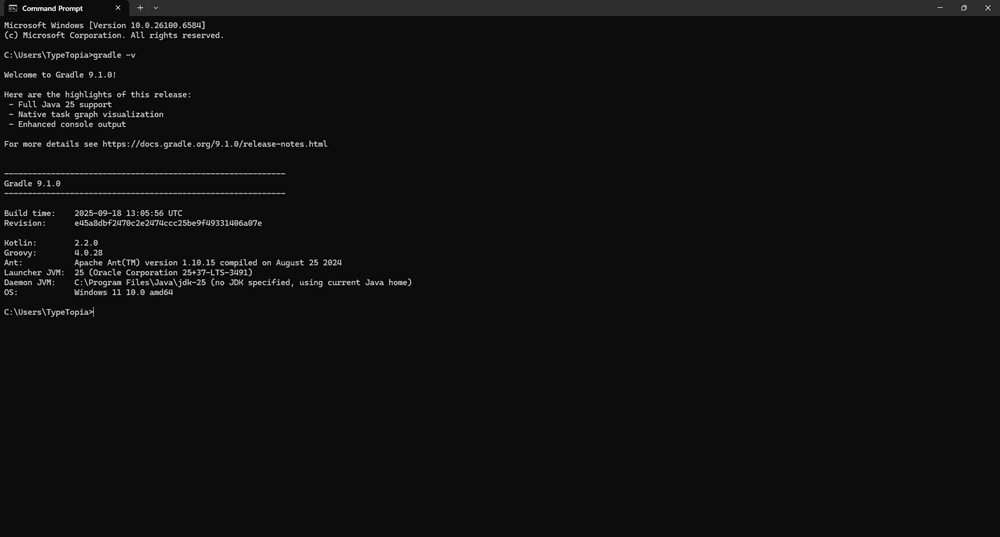

Step 7: Verify installation

Open a new Command Prompt and run:

gradle -v

You should see information about your current Gradle version, like so:

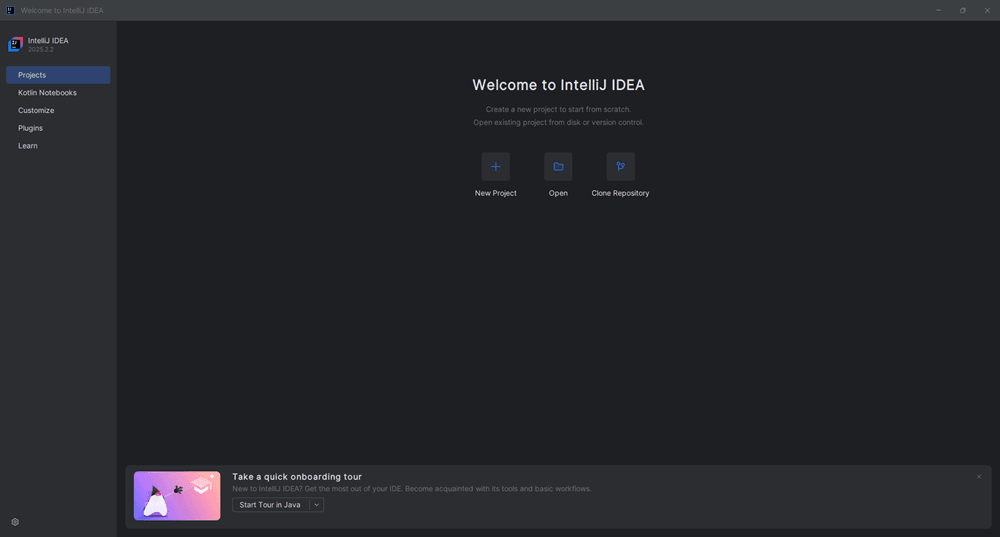

Which is the best IDE for Java web scraping?

Before we start coding, there’s one last thing to lock in: your Integrated Development Environment (IDE).

In Python, this wouldn’t be a big deal. You could write your script in any editor and run it from the terminal. But Java has rules. That’s why you need an IDE that can handle all of it for you.

The best option for web scraping with Java is IntelliJ IDEA. It’s the industry default for Java developers and makes your workflow faster, cleaner, and less error-prone.

There are two editions:

- Community edition (free)

- Perfect for building web scrapers

- Built-in support for Gradle, Maven

- Handles Java builds, error checking, and folder structure automatically

- Ultimate edition (paid)

- More suited to enterprise apps with heavy frameworks

- Not required for scraping web pages or managing scraping libraries

We’ll use IntelliJ IDEA Community Edition for this entire tutorial because it supports everything we need. Head to the JetBrains site, download the installer, and follow the prompts. Once installed, open your build.gradle file. IntelliJ will auto-import everything and prepare your web scraping environment.

Scraping static pages with Jsoup

Now we’re ready. Before writing any code, let’s get the syntax right. For static pages, we’ll use the Jsoup library. More on that in a moment, here’s how to get started:

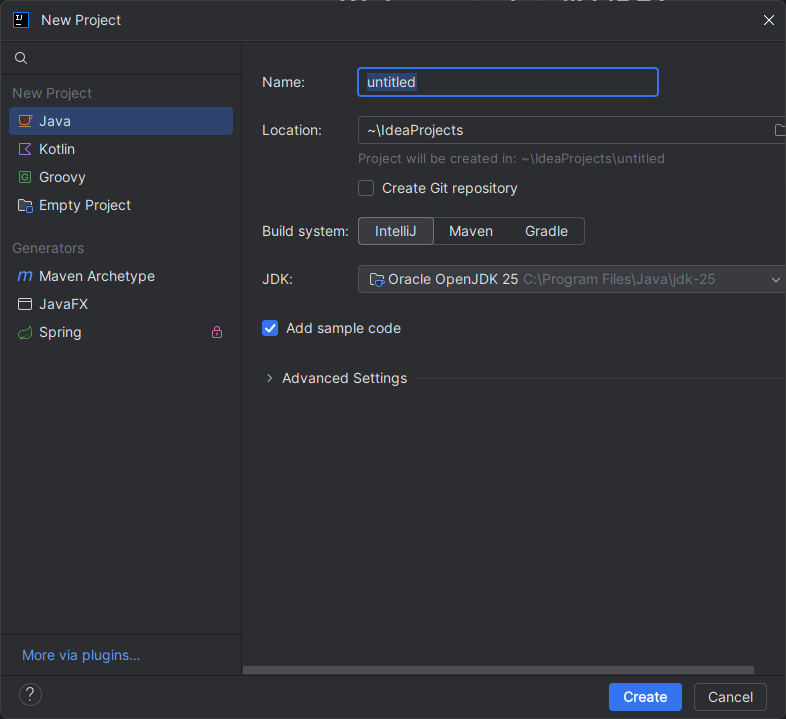

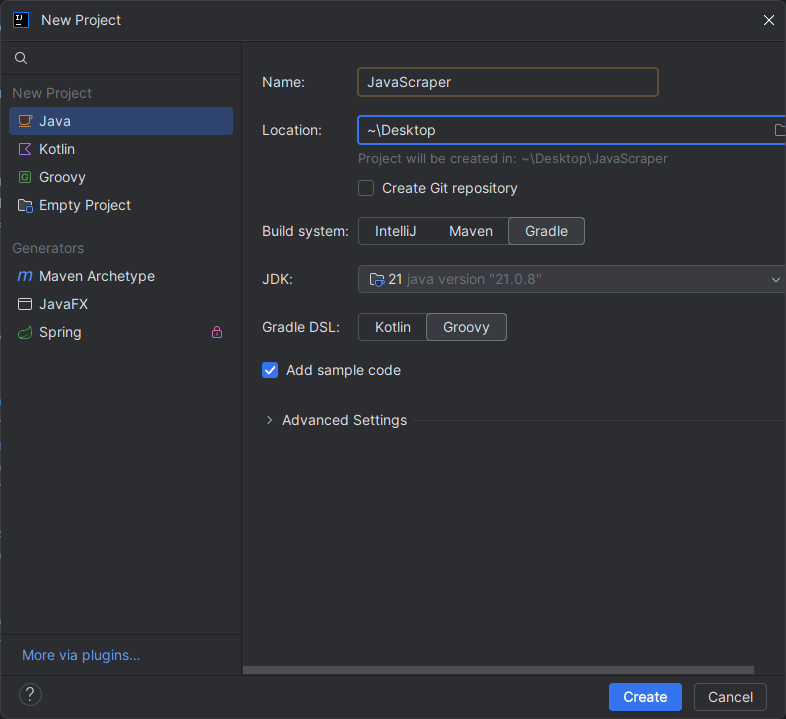

Step 1: Launch IntelliJ IDEA

Open IntelliJ IDEA.

Step 2: Start a new project

Select 'New Project'.

Step 3: Configure your project settings

Set:

- Name: JavaScraper

- Location: Desktop

- Build system: Choose Gradle

- JDK: Confirm it's what you installed earlier, Oracle OpenJDK 21

- Gradle DSL: Choose Groovy, it's simpler

Step 4: Create the project

Click 'Create'.

Step 5: Prepare to add dependencies

You are now ready to code.

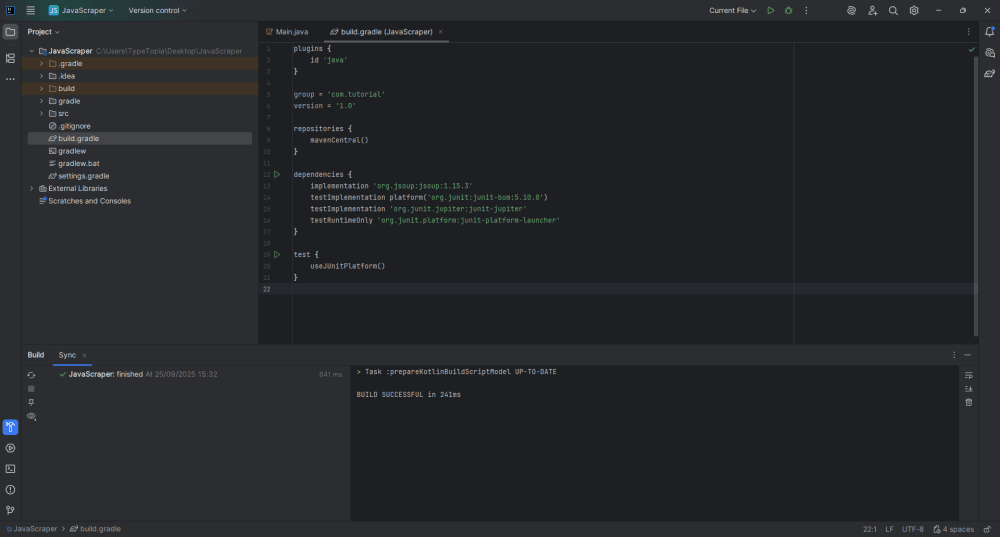

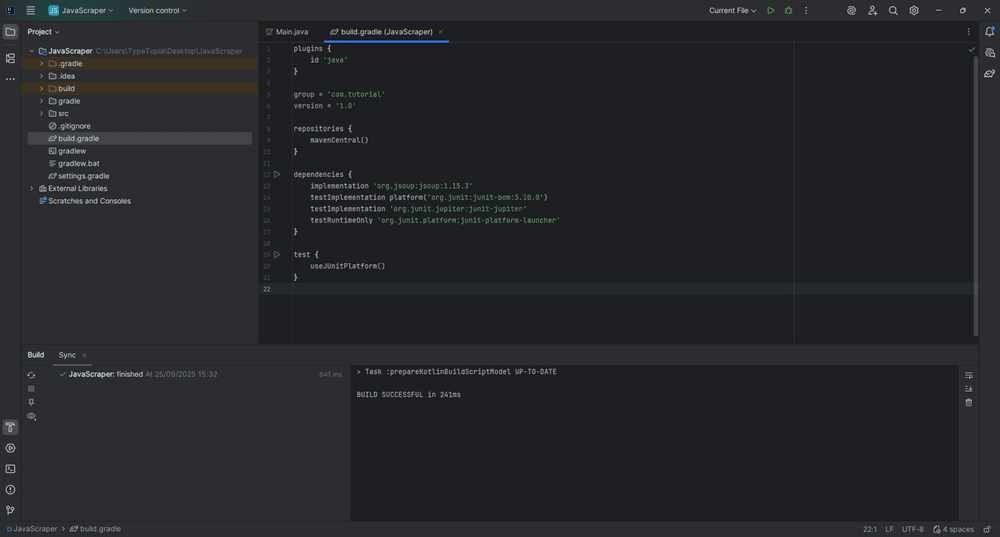

Step 6: Add Jsoup to build.gradle

In the top-left section of your screen under Project, locate the file named 'build.gradle' (it has a Gradle icon). Click to open it.

Replace the code with this:

plugins {

id 'java'

}

group = 'com.tutorial'

version = '1.0'

repositories {

mavenCentral()

}

dependencies {

implementation 'org.jsoup:jsoup:1.15.3'

}

Step 7: Sync your Gradle project

In the bottom-left corner, click the 'Sync now' icon to update your project.

Gradle will download the dependencies and let you know once the build is successful. That's it! You successfully installed Jsoup for scraping static content.

Handling dynamic content with Selenium

Jsoup is great when you're scraping static pages. It can fetch HTML data and parse it cleanly with element selectors. But that’s where it stops. Because Jsoup doesn’t execute JavaScript or track DOM changes, it can only parse the initial HTML and won’t retrieve elements rendered later in the load cycle.

So if you’re scraping pages that load data dynamically, Jsoup alone won’t get the job done. This is where Selenium becomes essential. It is a full browser automation tool that lets your Java scraper control a real or headless browser.

Selenium can simulate user behavior by:

- Scrolling the page

- Clicking buttons

- Submitting forms

- Waiting for AJAX calls to complete

- Pulling data from content that isn’t present in the original source code

For dynamic sites, this is the only way to perform reliable Java web scraping. Selenium supports both Chrome and Firefox, integrates smoothly with Java via the WebDriver API, and can work alongside Jsoup or other Java web scraping libraries to handle both static and dynamic content in the same scraping process.

Installing Selenium

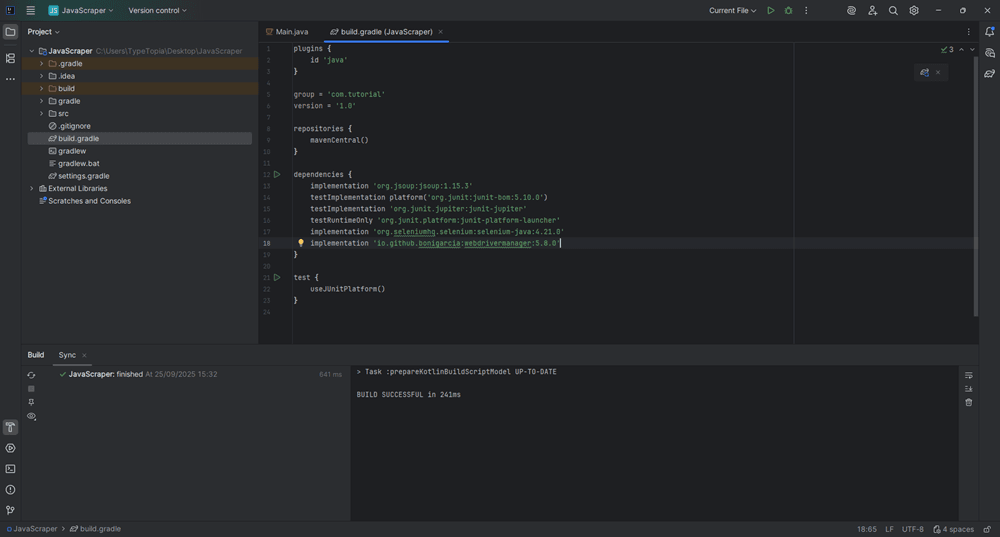

Step 1: Open build.gradle

In the top-left panel of IntelliJ IDEA, find and open build.gradle under the Project Tool Window (it has a Gradle icon next to it).

Step 2: Add Selenium and WebDriverManager dependencies

Next, scroll to the dependencies block and add the following:

implementation 'org.seleniumhq.selenium:selenium-java:4.21.0'

implementation 'io.github.bonigarcia:webdrivermanager:5.8.0'

Your code should now look like this:

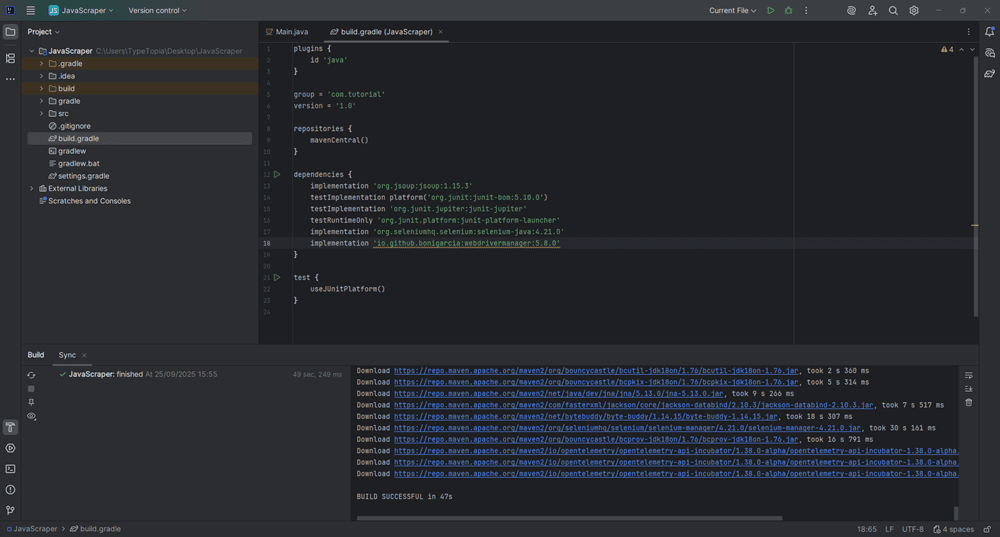

Step 3: Sync your Gradle project

Press the 'Sync' button for Gradle to download Selenium.

That's it! You now have the two tools we will use for web scraping with Java installed.

Top Java web scraping libraries compared

By now, you’ve seen how to set up Jsoup and Selenium. But Java offers more than just these two. Here's a breakdown of the top Java web scraping libraries, and when to reach for each one.

- Jsoup

Best for static HTML scraping. It’s fast, intuitive, and works well when the data is present in the initial page load. You can extract data using element selectors and process HTML content with ease. But it can’t execute JavaScript or wait for dynamic elements, so skip it for JavaScript-heavy pages.

- HtmlUnit

HtmlUnit mimics a headless browser and handles light JavaScript. It’s useful for simple dynamic sites that don’t depend on complex frontend logic. However, it’s known to struggle with modern web architectures, and its support for new APIs is limited. Think of it as a lightweight emulator, not a full browser.

- Selenium

When dynamic content is involved, Selenium becomes essential. It spins up a real browser or a headless browser and lets your web scraper interact with the page just like a human. It’s the preferred tool for extracting data from JavaScript-rendered pages or single-page applications (SPAs).

- WebMagic

If you’re building a scalable web scraper or distributed crawler, WebMagic is worth your time. It lets you configure page processors, thread pools, retry logic, pipelines, and scheduling workflows.

Here is a table comparing the Java web scraping libraries we discussed:

Use it when the data is in the page source and doesn’t require JS to appear.

Parses static HTML with element selectors. Great for clean markup and fast scrapes.

Cannot render or interact with JavaScript. Doesn’t load dynamic content.

Scraping blog posts, product listings, public tables, or sitemap-based pages.

Use when you need lightweight JS support but don’t want the full overhead of Selenium.

Executes some JavaScript. Emulates a headless browser without opening a UI.

Struggles with modern SPAs, AJAX-heavy sites, and complex frontend JS.

Login forms, small dynamic websites, or legacy apps with light interactivity.

Use when the site needs to load, scroll, click, or wait for JS to render before data appears.

Full browser control. Can simulate user actions, wait for elements, and handle SPAs.

Slower. Heavier resource use. Needs good proxy and anti-block strategies.

Scraping real-time prices, JS-heavy pages, infinite scroll feeds, or SPAs like React or Vue.

Use when you’re building a large-scale, multi-page crawler with logic, retries, and scale.

Handles pipelines, processors, retries, proxies, and multithreading - all built-in.

Learning curve. You still plug in Jsoup or Selenium for actual page interaction.

Building scrapers for news sites, e-commerce catalogs, lead lists, or crawling thousands of URLs.

Then press 'Enter' to create it. This file stores the list of residential proxies that your scraper will rotate through when scraping Hacker News.Real-world example: Scraping blog posts

Now we’re ready to get into the weeds of Java web scraping using everything we’ve built so far. We’re going to scrape data from Hacker News, a technology-focused news aggregation site created and maintained by Y Combinator. The goal is to extract blog-style post titles, links, and timestamps using a rotating proxy setup.

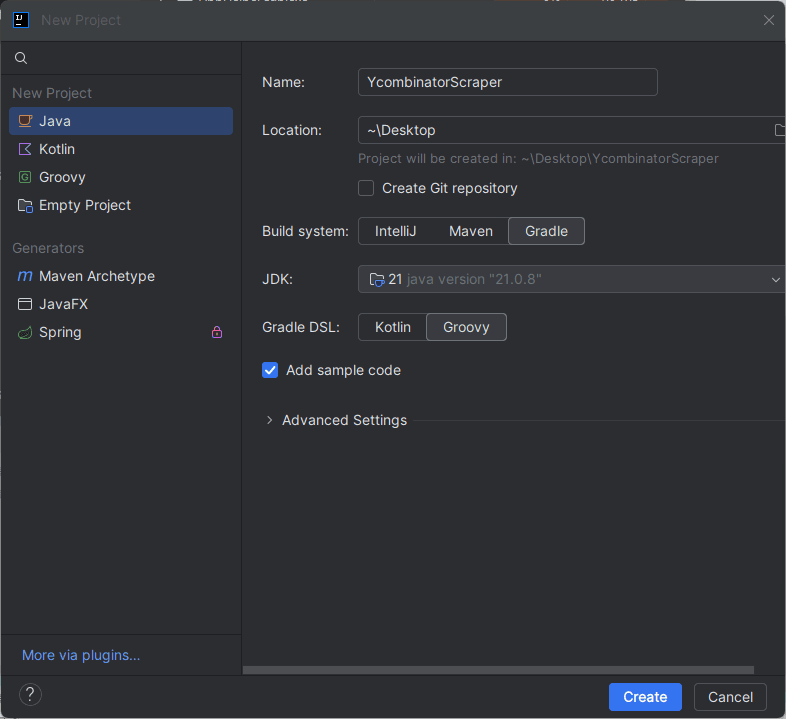

Step 1: Create a new project in IntelliJ IDEA

Open IntelliJ IDEA and create a new project.

Set the following options:

- Location: Choose your preferred folder (e.g., Desktop)

- Build system: Gradle

- Language: Java

- Project SDK: JDK 21

- Gradle DSL: Groovy

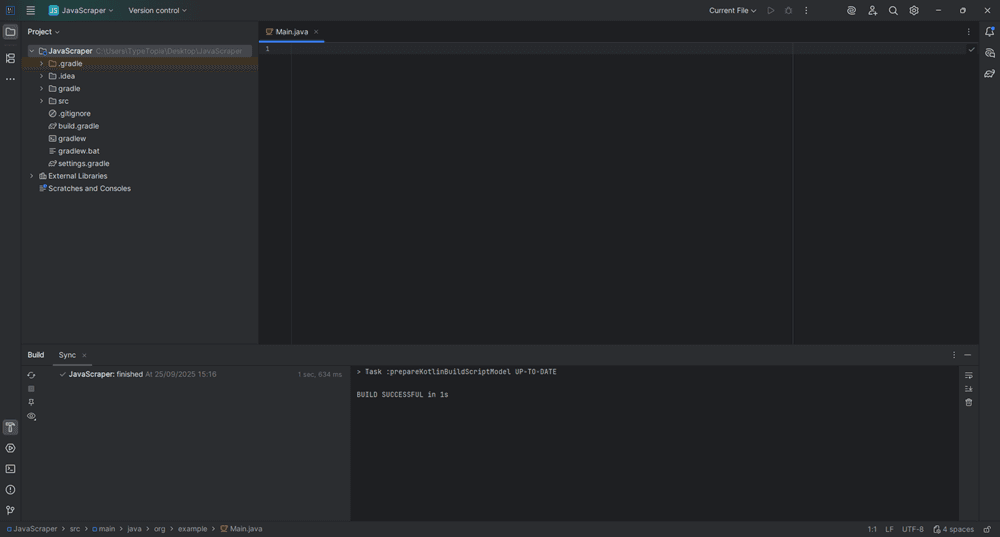

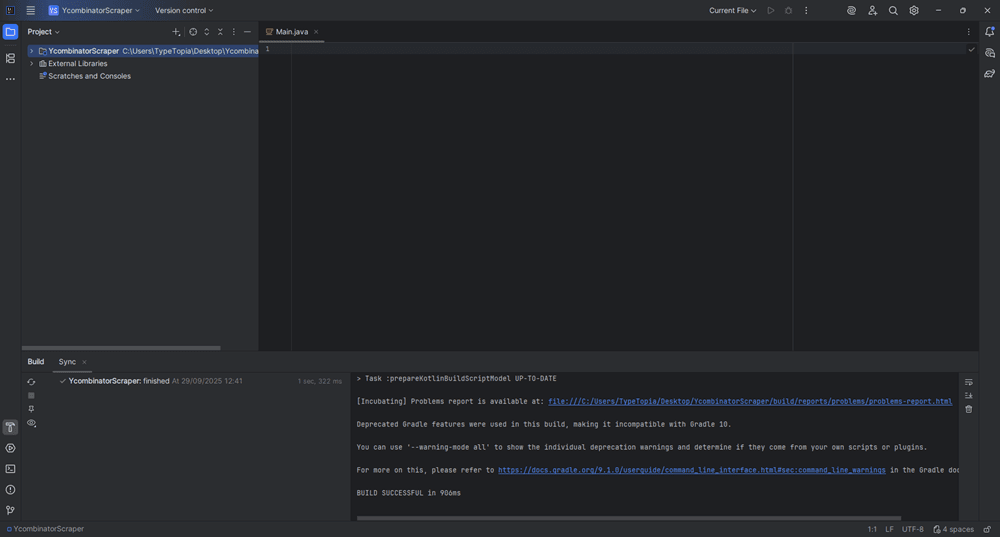

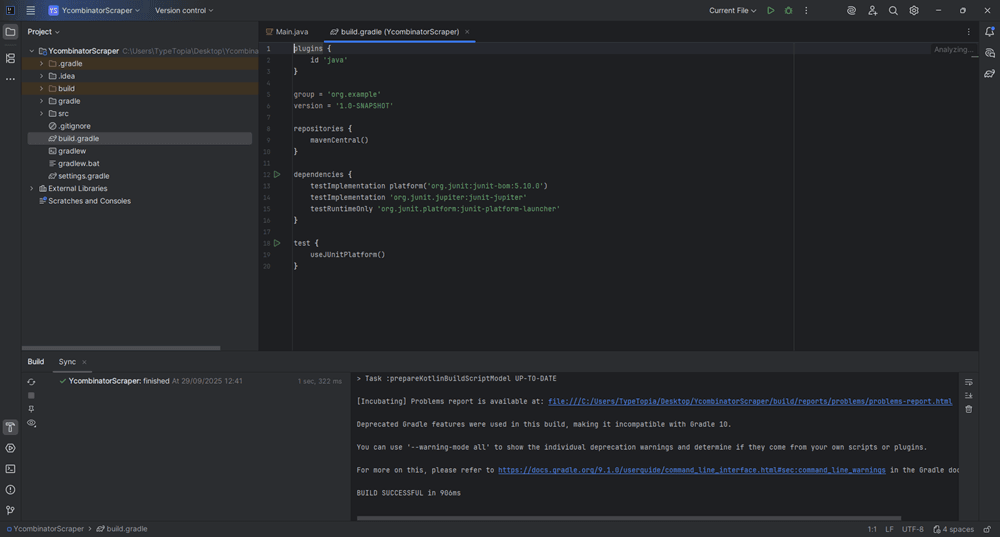

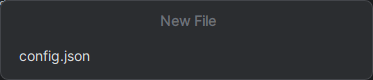

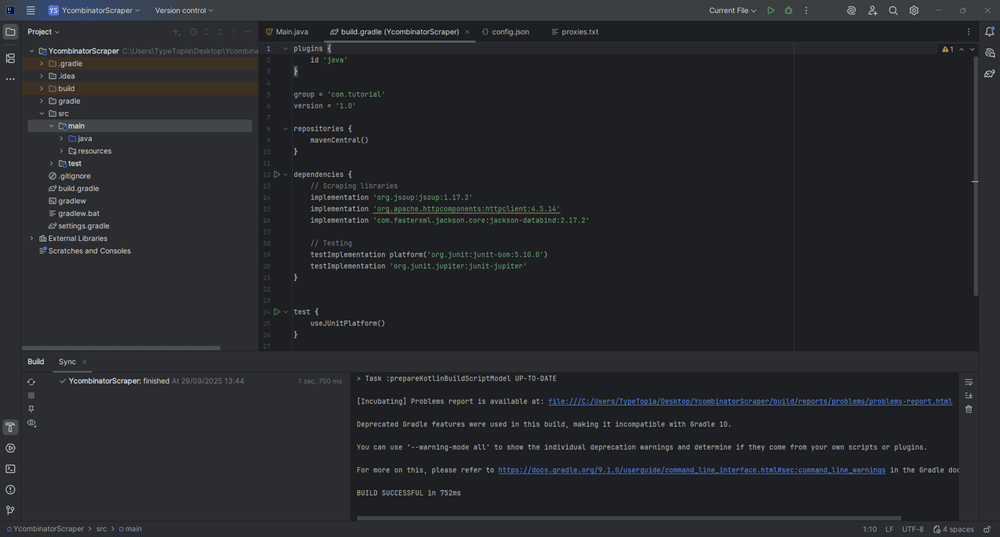

Click 'Create' to generate the project. You will be redirected to the following screen:

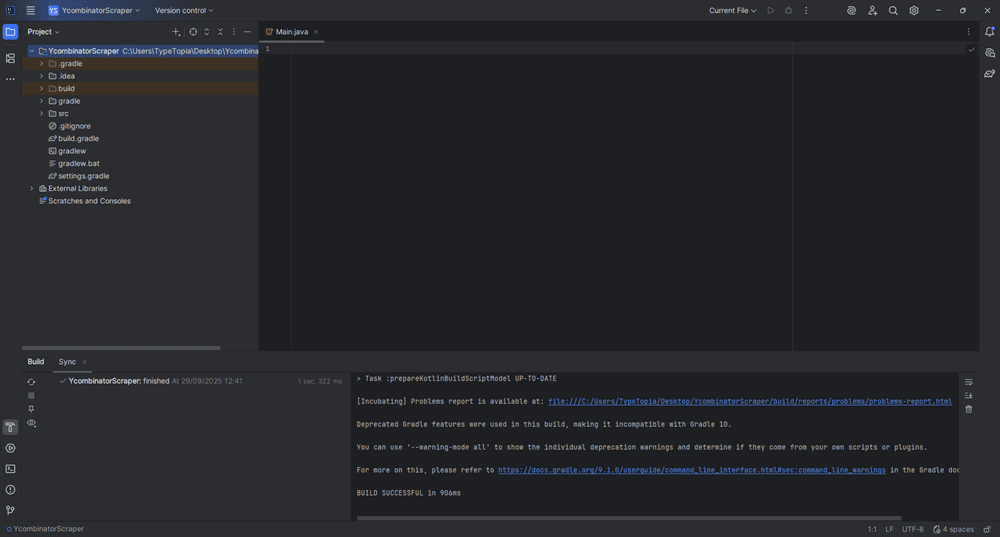

Step 2: Locate the project structure

In the Project Tool Window, expand the YcombinatorScraper folder to view the package layout.

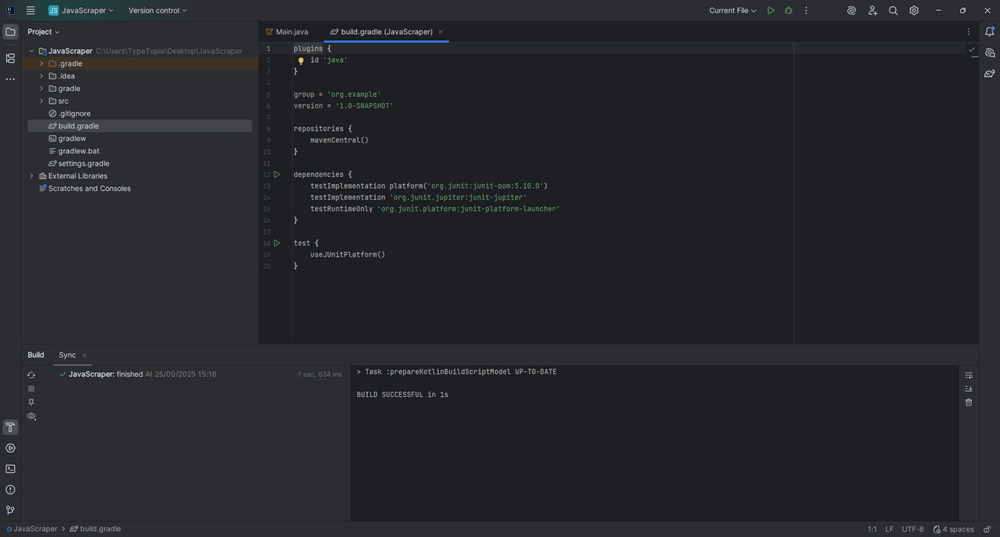

Step 3: Open the build.gradle file

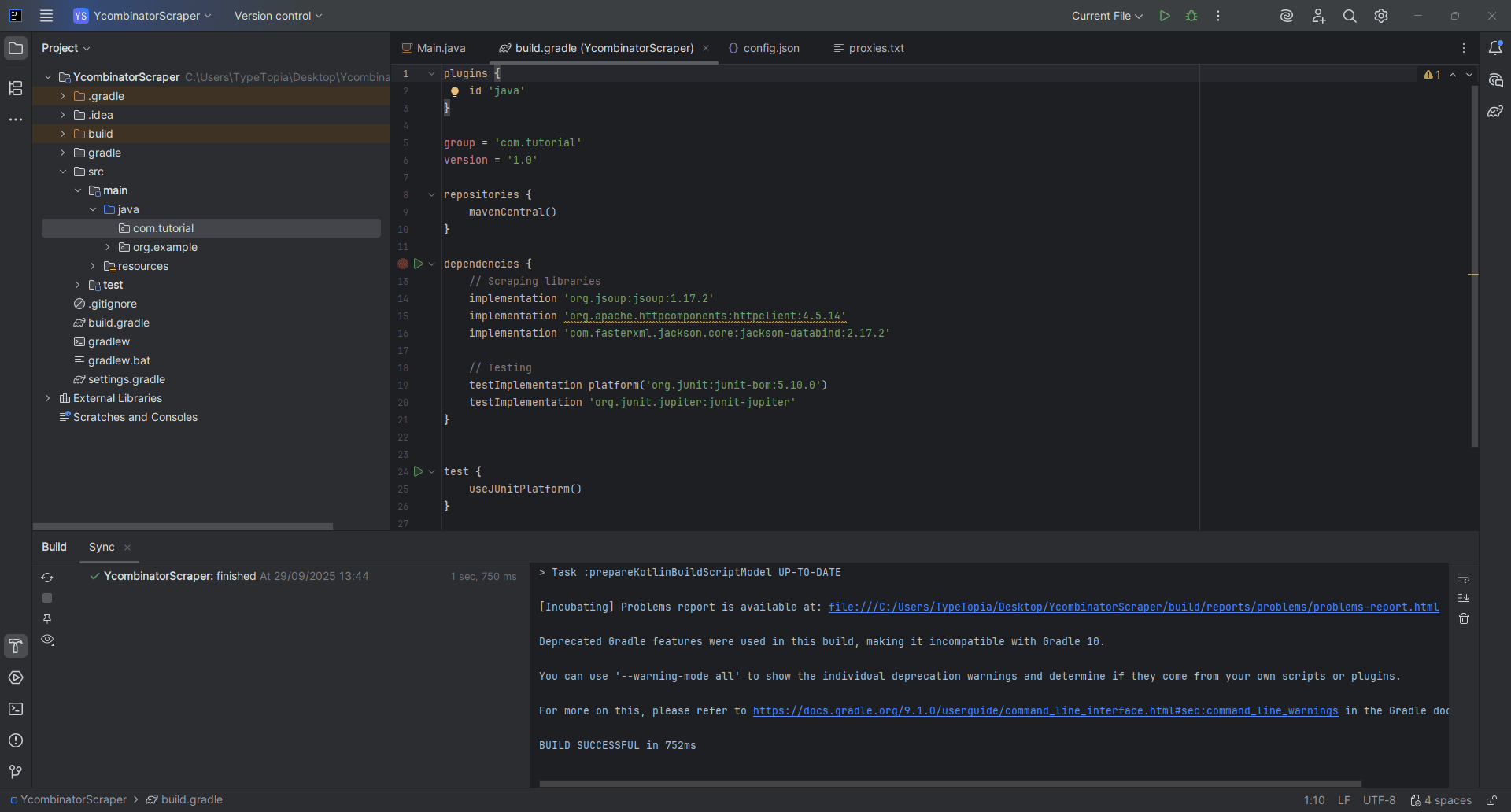

In the root of your project, find and open build.gradle.

Step 4: Add core libraries

We'll add three key libraries to our project:

- Jsoup: handles parsing and scraping HTML from our target site

- Apache HttpClient: enables HTTP requests with advanced control (headers, proxies, authentication)

- Jackson Databind: reads from and writes to JSON files like our config and proxy settings

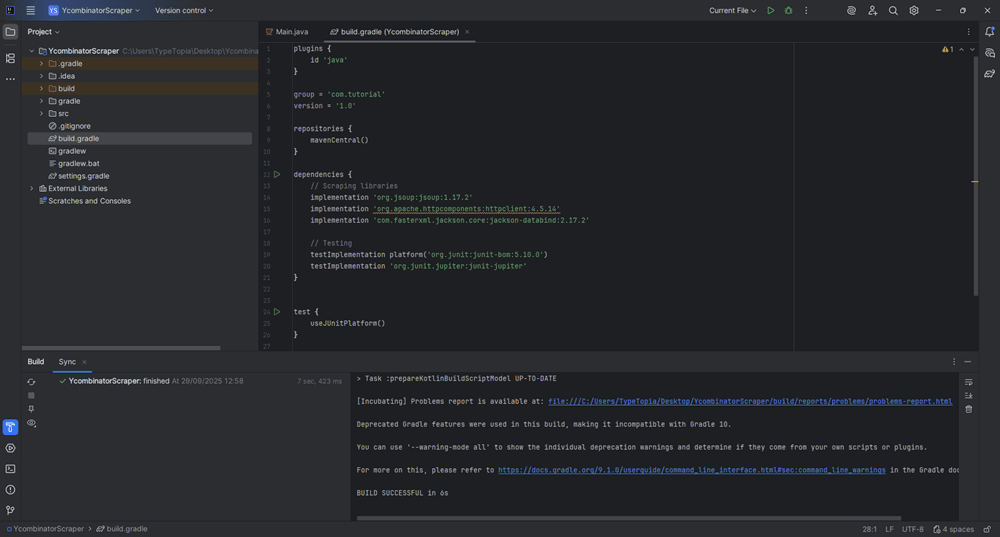

Replace the contents of build.gradle with:

plugins {

id 'java'

}

group = 'com.tutorial'

version = '1.0'

repositories {

mavenCentral()

}

dependencies {

// Scraping libraries

implementation 'org.jsoup:jsoup:1.17.2'

implementation 'org.apache.httpcomponents:httpclient:4.5.14'

implementation 'com.fasterxml.jackson.core:jackson-databind:2.17.2'

// Testing

testImplementation platform('org.junit:junit-bom:5.10.0')

testImplementation 'org.junit.jupiter:junit-jupiter'

}

test {

useJUnitPlatform()

}

Step 5: Sync Gradle

Click the 'Sync' icon in the Build tool window (bottom-right). You should see a “BUILD SUCCESSFUL” message.

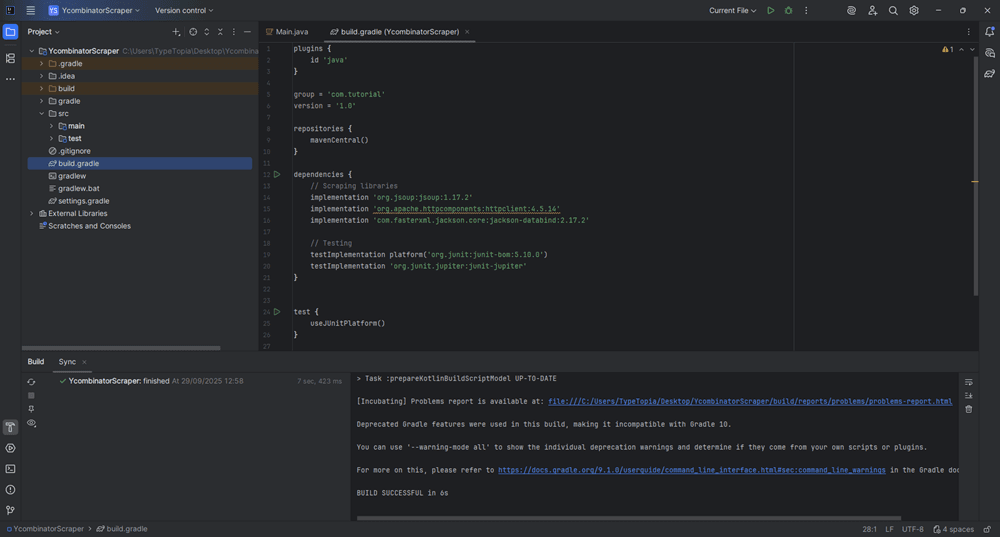

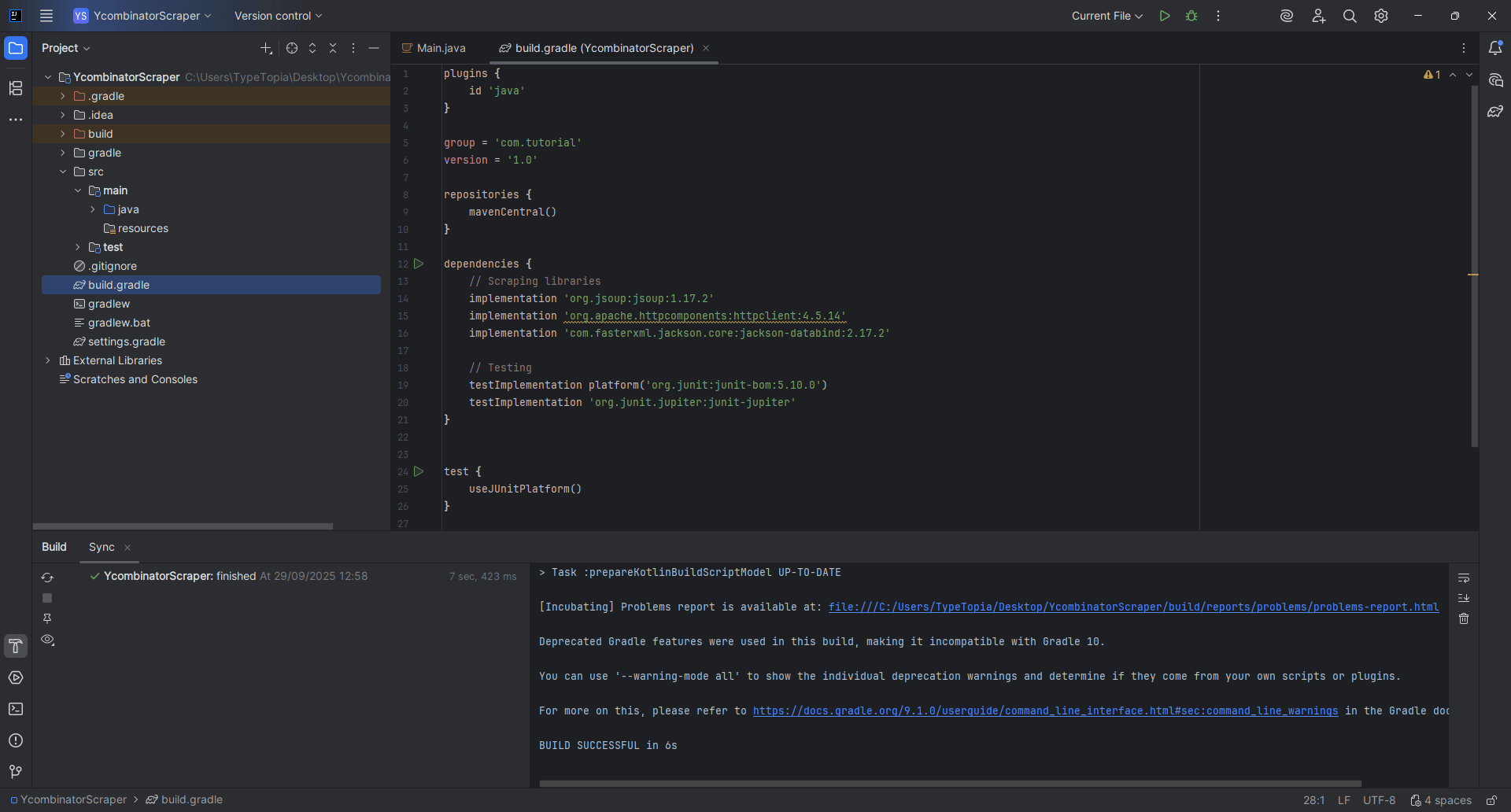

Step 6: Expand the src folder

In the Project tool window on the left, expand the src folder to reveal its contents.

Step 7: Locate the main directory

Click the arrow next to main to drop it down and show its subfolders:

- java

- resources

Step 8: Open the resources folder

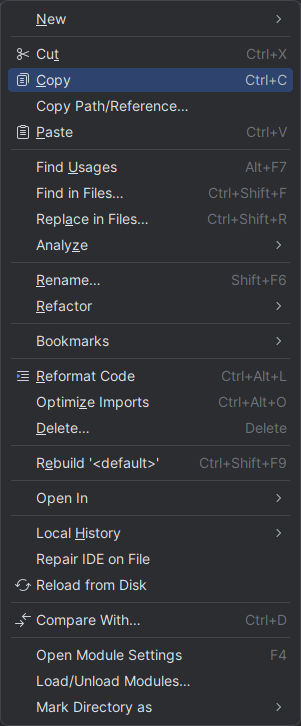

Right-click on the 'resources' folder.

Step 9: Create a new file

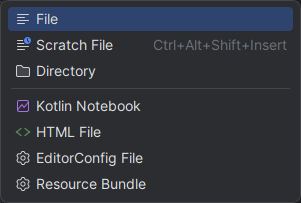

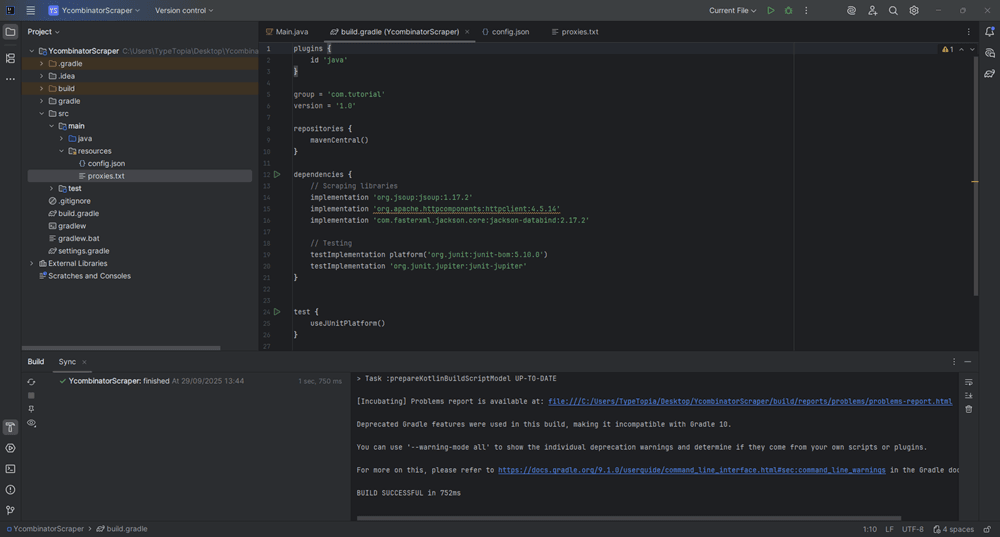

Hover over 'New', then click 'File' from the dropdown.

Step 10: Name the file config.json

Name the file exactly:

Step 11: Add your scraper configuration

Add the following into your new config.json file:

{

"startUrl": "https://news.ycombinator.com/",

"pages": 3,

"minDelayMs": 1200,

"maxDelayMs": 2500,

"retries": 3,

"output": "hn_results.csv",

"userAgent": "Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/124.0.0.0 Safari/537.36 OrinaScraper/1.0"

}

The config.json file is the brain of your scraper. It defines:

- Which website to scrape (startUrl)

- How many pages to crawl (pages)

- How long to wait between requests (minDelayMs and maxDelayMs)

- How many times to retry if a page fails (retries)

- Where to save your results (output)

- How your scraper identifies itself (userAgent)

You can tweak these settings anytime to change how your scraper behaves without touching the Java code.

Step 12: Create the proxies file

Right-click the resources folder again and repeat the same steps:

- Hover over 'New'

- Click 'File'

- Name the file:

proxies.txt

Then press 'Enter' to create it. This file stores the list of residential proxies that your scraper will rotate through when scraping Hacker News.

Step 13: Add proxy entries

We’re using five authenticated Residential Proxies from MarsProxies, each with a different location and session ID:

ultra.marsproxies.com:44443:mr45184psO8:MKRYlpZgSa_country-us_city-losangeles_session-j1ko4q46_lifetime-30m

ultra.marsproxies.com:44443:mr45184psO8:MKRYlpZgSa_country-us_state-alaska_session-v750sry6_lifetime-30m

ultra.marsproxies.com:44443:mr45184psO8:MKRYlpZgSa_country-us_state-kansas_session-afxhhuv5_lifetime-30m

ultra.marsproxies.com:44443:mr45184psO8:MKRYlpZgSa_country-us_state-maryland_session-u8sgsjv6_lifetime-30m

ultra.marsproxies.com:44443:mr45184psO8:MKRYlpZgSa_country-us_city-oakland_session-qlzwp7xo_lifetime-30m

Read this guide for more information on how to use MarsProxies Residential Proxies.

Step 14: Sync Gradle again

By now, you should have two files inside the resources folder:

- config.json: defines scraper settings

- proxies.txt: holds proxy credentials

Head back to the Build tool window in the bottom-right and click the 'sync' icon again. If everything is correct, IntelliJ will show: BUILD SUCCESSFUL.

Step 15: Prepare to add Java code

Now that our config.json and proxies.txt files are ready, it’s time to wire in the actual scraping logic. Start by creating a new Java class.

Expand 'main' in the Project tool window:

Step 16: Create a new package

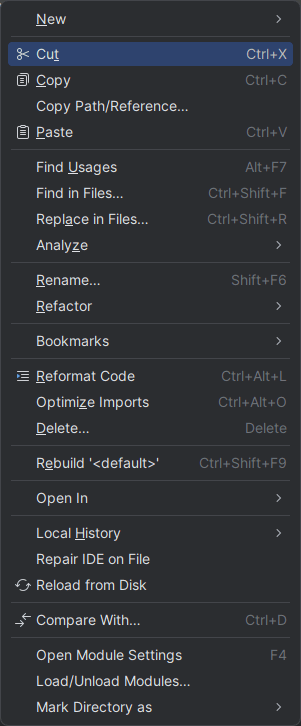

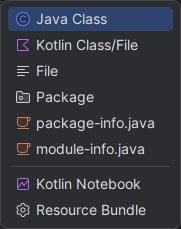

Right-click on Java to reveal options.

Click on 'New' and select 'Package'.

Name the new package exactly:

com.tutorial

You should now have a new package under Java.

Step 17: Add a new Java class

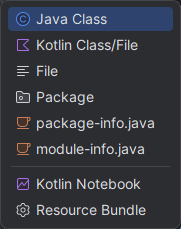

Right-click on the new package com.tutorial.

Step 18: Name the class

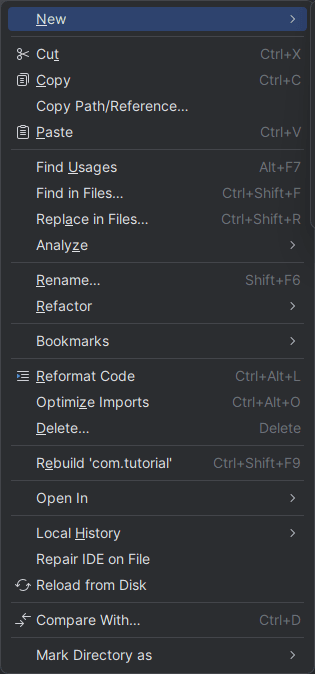

Hover over 'New' to reveal the following dropdown list:

Select 'Java Class' and name the new class:

Ycombinatorblogpostextractor

Step 19: Add the scraper code

Paste the full HackerNewsScraper class into your new Java file. This includes configuration handling, proxy support, scraping logic, and utility functions.

package com.tutorial;

import com.fasterxml.jackson.databind.JsonNode;

import com.fasterxml.jackson.databind.ObjectMapper;

import org.apache.http.HttpHost;

import org.apache.http.auth.AuthScope;

import org.apache.http.auth.UsernamePasswordCredentials;

import org.apache.http.client.CredentialsProvider;

import org.apache.http.client.methods.CloseableHttpResponse;

import org.apache.http.client.methods.HttpGet;

import org.apache.http.impl.client.BasicCredentialsProvider;

import org.apache.http.impl.client.CloseableHttpClient;

import org.apache.http.impl.client.HttpClients;

import org.apache.http.impl.conn.DefaultProxyRoutePlanner;

import org.apache.http.util.EntityUtils;

import org.jsoup.Jsoup;

import org.jsoup.nodes.Document;

import org.jsoup.nodes.Element;

import java.io.*;

import java.nio.charset.StandardCharsets;

import java.security.SecureRandom;

import java.util.*;

import java.util.concurrent.ThreadLocalRandom;

import java.util.concurrent.atomic.AtomicInteger;

import java.util.stream.Collectors;

public class HackerNewsScraper {

// Config

static class Config {

String startUrl;

int pages;

int minDelayMs;

int maxDelayMs;

int retries;

String output;

String userAgent;

}

// Proxy entry

static class ProxyEntry {

final String host;

final int port;

final String username;

final String password; // may include session + geo tokens (keep as-is)

final String label;

ProxyEntry(String host, int port, String username, String password, String label) {

this.host = host; this.port = port; this.username = username; this.password = password; this.label = label;

}

static ProxyEntry parse(String line) {

// Expect format host:port:user:passWithSessionAndFlags

String[] parts = line.trim().split(":", 4);

if (parts.length < 4) throw new IllegalArgumentException("Bad proxy line: " + line);

String host = parts[0];

int port = Integer.parseInt(parts[1]);

String user = parts[2];

String pass = parts[3];

// derive a short label from any _city- or _state- token if present

String label = "proxy";

int cityIdx = pass.indexOf("_city-");

int stateIdx = pass.indexOf("_state-");

if (cityIdx >= 0) {

String rest = pass.substring(cityIdx + 6);

label = rest.split("[_\\s]")[0];

} else if (stateIdx >= 0) {

String rest = pass.substring(stateIdx + 7);

label = rest.split("[_\\s]")[0];

}

return new ProxyEntry(host, port, user, pass, label);

}

}

private final Config cfg;

private final List<ProxyEntry> proxies;

private final AtomicInteger rr = new AtomicInteger(0);

private final SecureRandom rng = new SecureRandom();

public HackerNewsScraper(Config cfg, List<ProxyEntry> proxies) {

this.cfg = cfg; this.proxies = proxies;

if (proxies.isEmpty()) throw new IllegalStateException("No proxies loaded");

}

public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception {

Config cfg = loadConfig();

List<ProxyEntry> proxies = loadProxies();

HackerNewsScraper app = new HackerNewsScraper(cfg, proxies);

app.scrape();

}

private void scrape() throws Exception {

try (PrintWriter out = new PrintWriter(new OutputStreamWriter(new FileOutputStream(cfg.output), StandardCharsets.UTF_8)))

out.println("postId,rank,title,link,timeText,timeISO,commentsCount,commentsUrl");

String url = cfg.startUrl;

for (int p = 1; p <= cfg.pages; p++) {

Document doc = getWithRetries(url);

if (doc == null) throw new IOException("Failed to fetch: " + url);

// Parse items on the page

for (Element row : doc.select("tr.athing")) {

String postId = row.attr("data-id").trim();

// HN uses <span class="titleline"><a ...> now; keep fallback for .storylink

Element titleA = Optional.ofNullable(row.selectFirst("span.titleline > a"))

.orElse(row.selectFirst(".storylink"));

if (titleA == null) continue;

String title = titleA.text();

String link = titleA.attr("href");

Element metaRow = row.nextElementSibling();

String timeText = "";

String timeISO = "";

int commentsCount = 0;

String commentsUrl = "";

if (metaRow != null) {

Element sub = metaRow.selectFirst(".subtext");

if (sub != null) {

Element age = sub.selectFirst(".age a");

if (age != null) {

timeText = age.text();

// 'title' attribute contains absolute time (e.g., 2025-09-29T08:12:34)

timeISO = age.attr("title");

}

List<Element> itemLinks = sub.select("a[href^=item?id]");

if (!itemLinks.isEmpty()) {

Element c = itemLinks.get(itemLinks.size() - 1);

commentsUrl = abs("https://news.ycombinator.com/", c.attr("href"));

String txt = c.text();

if (txt.matches(".*\\d+.*")) {

String digits = txt.replaceAll("\\D+", "");

if (!digits.isEmpty()) commentsCount = Integer.parseInt(digits);

} else {

commentsCount = 0; // "discuss"

}

}

}

}

String rank = row.selectFirst("span.rank") != null ? row.selectFirst("span.rank").text() : "";

out.printf(Locale.ROOT,

"%s,%s,\"%s\",%s,%s,%s,%d,%s%n",

csv(postId), csv(rank), csv(title), csv(link), csv(timeText), csv(timeISO), commentsCount, csv(commentsUrl));

}

// Find pagination (More)

Element more = doc.selectFirst("a.morelink");

if (p < cfg.pages && more != null) {

url = abs(cfg.startUrl, more.attr("href"));

sleepJitter(cfg.minDelayMs, cfg.maxDelayMs);

} else {

break;

}

}

}

System.out.println("Done. Wrote " + cfg.output);

}

// --- Networking with rotating proxies ---

private Document getWithRetries(String url) {

int attempts = 0;

while (attempts < cfg.retries) {

ProxyEntry px = pickProxy();

try {

Document d = fetchViaProxy(px, url);

if (d != null) return d;

} catch (Exception e) {

// log and fall through to retry with next proxy

System.err.println("[WARN] " + px.label + " failed: " + e.getMessage());

}

attempts++;

sleep(cfg.minDelayMs + 400L);

}

return null;

}

private ProxyEntry pickProxy() {

int i = Math.floorMod(rr.getAndIncrement(), proxies.size());

return proxies.get(i);

}

private Document fetchViaProxy(ProxyEntry px, String url) throws Exception {

CredentialsProvider credsProvider = new BasicCredentialsProvider();

credsProvider.setCredentials(new AuthScope(px.host, px.port), new UsernamePasswordCredentials(px.username, px.password));

HttpHost proxy = new HttpHost(px.host, px.port);

DefaultProxyRoutePlanner routePlanner = new DefaultProxyRoutePlanner(proxy);

try (CloseableHttpClient client = HttpClients.custom()

.setDefaultCredentialsProvider(credsProvider)

.setRoutePlanner(routePlanner)

.build()) {

HttpGet get = new HttpGet(url);

get.setHeader("User-Agent", cfg.userAgent);

get.setHeader("Accept", "text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,*/*;q=0.8");

get.setHeader("Accept-Encoding", "gzip, deflate");

get.setHeader("Accept-Language", "en-US,en;q=0.9");

try (CloseableHttpResponse resp = client.execute(get)) {

int status = resp.getStatusLine().getStatusCode();

if (status >= 200 && status < 300) {

String html = EntityUtils.toString(resp.getEntity(), StandardCharsets.UTF_8);

return Jsoup.parse(html, url);

}

throw new IOException("HTTP " + status);

}

}

}

// --- Utilities ---

private static String abs(String base, String href) {

try { return new java.net.URL(new java.net.URL(base), href).toString(); }

catch (Exception e) { return href; }

}

private static String csv(String s) {

if (s == null) return "";

String t = s.replace("\"", "\"\"");

if (t.contains(",") || t.contains("\n") || t.contains("\"")) return '"' + t + '"';

return t;

}

private void sleepJitter(int minMs, int maxMs) {

int delta = Math.max(0, maxMs - minMs);

int wait = minMs + (delta == 0 ? 0 : ThreadLocalRandom.current().nextInt(delta));

sleep(wait);

}

private void sleep(long ms) {

try { Thread.sleep(ms); } catch (InterruptedException ignored) { }

}

private static Config loadConfig() throws IOException {

ObjectMapper om = new ObjectMapper();

try (InputStream in = HackerNewsScraper.class.getClassLoader().getResourceAsStream("config.json")) {

if (in == null) throw new FileNotFoundException("config.json not found in resources");

JsonNode node = om.readTree(in);

Config c = new Config();

c.startUrl = node.get("startUrl").asText();

c.pages = node.get("pages").asInt(1);

c.minDelayMs = node.get("minDelayMs").asInt(1200);

c.maxDelayMs = node.get("maxDelayMs").asInt(2500);

c.retries = node.get("retries").asInt(3);

c.output = node.get("output").asText("hn_results.csv");

c.userAgent = node.get("userAgent").asText("Mozilla/5.0 OrinaScraper");

return c;

}

}

private static List<ProxyEntry> loadProxies() throws IOException {

InputStream in = HackerNewsScraper.class.getClassLoader().getResourceAsStream("proxies.txt");

if (in == null) throw new FileNotFoundException("proxies.txt not found in resources");

List<String> lines;

try (BufferedReader br = new BufferedReader(new InputStreamReader(in, StandardCharsets.UTF_8))) {

lines = br.lines().map(String::trim).filter(s -> !s.isEmpty() && !s.startsWith("#")).collect(Collectors.toList());

}

List<ProxyEntry> list = new ArrayList<>();

for (String line : lines) list.add(ProxyEntry.parse(line));

return list;

}

}

Let's take a moment to understand how this Java class works.

Package declaration

The first line of our code,

package com.tutorial;

defines the Java package this class belongs to. It tells the compiler and IntelliJ where to find the file in the src/main/java/com/tutorial folder. This is why we created that nested folder earlier: the package name and the folder structure must match.

Imports

Next come the import statements. Java requires you to declare every external class you plan to use. This is different from Python, where a single import often pulls in a whole module. In our scraper, we import:

- Jackson (JsonNode, ObjectMapper) reads config.json and turns its fields into usable Java objects.

- Apache HttpClient (HttpHost, AuthScope, CredentialsProvider, etc.) builds HTTP requests, sets headers, and routes traffic through proxies.

- Jsoup (Jsoup, Document, Element) parses the HTML returned from Hacker News so we can extract titles, timestamps, and comments.

- Java standard library classes: input/output, character sets, random numbers, thread‑safe counters, and collections for managing state.

Together, these imports bring in the tools our scraper needs.

Internal helper classes: Config and ProxyEntry

The next section of the code defines two internal helper classes. The first, Config, consolidates the core settings from config.json into a single Java object.

It holds fields for the start URL, number of pages to scrape, delay intervals between requests, retry count, output file name, and the user-agent string. By wrapping all these fields into one class, we keep the configuration data structured and accessible throughout the scraper.

After that, we define the ProxyEntry class, which models a single proxy server. Each line in proxies.txt is parsed into this class, splitting the string into host, port, username, password, and a label.

The label is auto-generated from any city- or state-token in the password string, making it easier to identify which proxy is in use when rotating connections.

Persistent variables and constructor

After defining the helper classes, the scraper creates two persistent variables: one for configuration and another for proxies. The cfg field holds all the settings we loaded from config.json, including the start URL, delay timing, retry count, and output file.

Instead of reading from the file each time we need a value, the scraper keeps everything in memory and refers to cfg directly. The same pattern applies to proxies.

Each line from proxies.txt is parsed once and stored as a ProxyEntry object in the proxies list. This makes proxy rotation seamless. After loading both the scraper configuration and proxy list, the program initializes by passing those values into the constructor.

Main method and scraping loop

From there, the main() method triggers the entire scraping process by calling scrape(). The method begins by opening a CSV writer and creating a header row. It then loops through the number of pages specified in the config, starting with the base URL.

For each page, it attempts to download HTML using getWithRetries(), which handles proxy rotation and retry logic. If the request succeeds, the scraper parses each post by extracting the post ID, title, link, timestamp, and comment metadata. It writes these details to the CSV.

If a "More" link is detected, the scraper queues up the next page, applies a randomized delay, and continues. If the link is missing or the page limit is reached, the loop exits. Once all pages are processed, the CSV file is finalized, and the program prints a “Done” message to confirm completion.

Networking with rotating proxies

Each time it needs a page, getWithRetries loops through a fixed number of attempts defined in the config. It picks a proxy from the pool in round‑robin order so no single proxy is overused, then calls fetchViaProxy to send the HTTP request.

Apache HttpClient manages the proxy credentials and routing, while Jsoup parses the returned HTML into a usable Document. By isolating these steps, the scraper separates networking and proxy logic from the parsing logic, making the main scraping loop simpler and more reliable.

Utility functions

Finally, the scraper relies on small helper functions:

- abs() resolves relative links into absolute URLs

- csv() formats strings for safe CSV output

- sleepJitter() and sleep() add randomized or fixed delays between requests

- loadConfig() reads config.json and builds the Config object

- loadProxies() reads proxies.txt and turns each line into a ProxyEntry

These utilities handle the behind-the-scenes details, keeping navigation reliable, output safe, and requests human-like.

Step 20: Run the code

To run the scraper, look toward the top of your IntelliJ IDEA window. You’ll see a green play button next to the currently open file. This runs the main() method in your Java class. Click that button to compile and execute the program.

IntelliJ will launch your scraper using the config and proxy files you added earlier, then begin writing results to the output CSV specified in config.json.

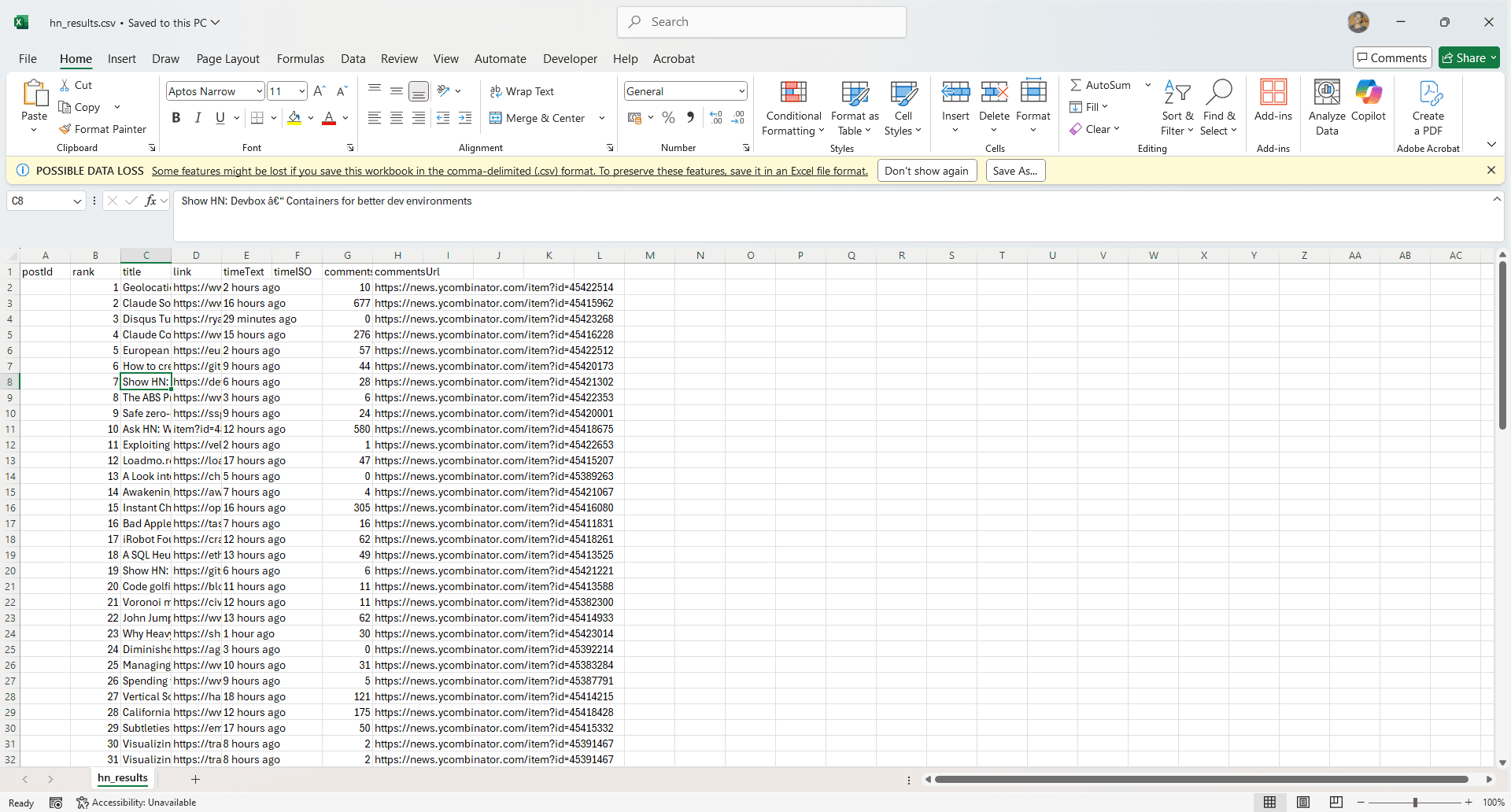

Step 21: Verify the scraped data

After running your scraper, open the folder where your project is saved. You should find a file called hn_results.csv. This file contains the raw output from your scraping session.

When you open it, you’ll see each blog-style post from Hacker News organized into columns:

- Post ID

- Rank, title

- Direct link

- Relative time

- ISO timestamp

- Number of comments

- Comments URL

If these values appear as expected, your scraper is working correctly.

Best practices + staying ethical

You know how to build a fully customized scraper in Java, whether you’re using Jsoup for static HTML or Selenium for dynamic content. But when it comes to scraping pages protected by aggressive bot detection, Java isn’t the most efficient tool. Python handles that kind of work with less friction and cleaner support libraries.

Still, even in Java, it’s good practice to rotate both proxies and user-agents to reduce your chances of getting blocked. The code we’ve already built includes basic error handling to help you retry failed requests without crashing the whole process.

But technical strategies alone aren’t enough. You should also follow ethical scraping principles: always respect a website’s robots.txt file and avoid extracting data from pages that explicitly disallow it.

Final tips & takeaways

That’s it. If you’ve made it this far, you now know how to build a scraper in Java, where it performs best, and where it makes more sense to switch to Python.

Java isn’t the fastest tool for rapid prototyping, but when you’re working inside an enterprise system or scraping structured data at scale, especially from legacy systems, it offers real advantages. Just remember to stay practical about what it can and can’t do.

Ready for more tips on scraping with Java? Join our Discord community.

How do you manage session cookies and authentication in Java web scraping?

Use an HTTP client that preserves cookies across requests, for example, Apache HttpClient with a CookieStore or OkHttp with a CookieJar. Perform the login step first by POSTing credentials and any hidden form fields, capture the Set-Cookie headers or let the client store them automatically, then reuse the same client or cookie context for subsequent requests so the server recognizes your session.

How can I bypass CAPTCHAs when scraping with Java?

The pragmatic approach is to use a headless browser such as Selenium to render the page and then integrate a third-party CAPTCHA-solving API (for example, 2Captcha or Anti-Captcha): send the site key and page URL to the solver, poll for a token, and inject that token into the page or form before submitting. For image CAPTCHAs, you must capture the image and forward it to the solver, then apply the returned answer.

What’s the difference between web scraping and web crawling in Java?

Scraping means extracting structured data from a set of pages, while crawling means discovering and fetching pages by following links. A scraper in Java often uses Jsoup or HttpClient to fetch known URLs and process HTML. A crawler adds URL management, deduplication (sets or Bloom filters), politeness (robots.txt, rate limits), and scheduling or distributed workers.

How do you handle pagination and infinite scroll in Java web scraping?

For numbered or offset pagination, detect the URL pattern and iterate programmatically, fetching each page with Jsoup or your HTTP client and parsing the same selectors repeatedly.

How can I simulate browser behavior (headers, delays, mouse movements) in Java scraping?

Start by matching common request headers and Origin on each request. Also, rotate user-agents when appropriate. Add randomized delays and jitter between actions using ThreadLocalRandom to avoid fixed timing patterns, and respect robots.txt and rate limits to remain polite.