When it comes to parsing HTML and XML content in Python, the lxml library stands out as a powerful tool for the task. In this Python lxml tutorial, we'll explore how to use lxml for both web scraping tasks and XML processing. We’ll cover everything from installation and basic parsing to advanced techniques like XPath and CSS selectors.

Don't worry, we’ll break down each concept step by step. Whether you're extracting info from HTML documents on the web or manipulating XML documents behind the scenes, this guide will help you get the most out of the Python lxml library.

What is lxml and why use it?

lxml is a Python library for processing HTML and XML data. It combines the user-friendly API of Python’s built-in ElementTree with the speed of C libraries (it’s built on the renowned libxml2 and libxslt). This gives lxml both simplicity and performance. In practical terms, lxml lets you parse and create html or XML documents very efficiently.

Benefits of lxml over other libraries include:

- High performance

Because lxml uses optimized C code under the hood (libxml2 for parsing and libxslt for XSLT support), it’s fast and memory-efficient even on large or complex documents. This makes it ideal when you need to extract data from multiple pages or large XML files quickly.

- Rich feature set

The lxml library supports advanced features like full XPath 1.0 support, XSLT transformations, and XML Schema validation. In contrast, Python’s built-in xml.etree has only basic parsing and limited XPath.

- Flexibility with HTML and XML

lxml can handle both well-formed XML documents and real-world (often messy) HTML documents. It features an etree module for XML and an html module for HTML, providing you with tools tailored to each format. For example, you can use lxml import etree for strict XML parsing and lxml import HTML for forgiving HTML parsing.

- When to use lxml

Choose lxml when your project involves parsing HTML pages from the web (web scraping!), when working with XML file data, or whenever performance is important. If you need to extract data with complex queries or from lots of pages, lxml is a great choice. It’s widely used in production scraping environments because of its speed and reliability.

Compared to other options, lxml often hits a sweet spot. Pure Python parsers like BeautifulSoup are very easy to use and forgiving with bad HTML, but they are slower. The built-in xml.etree is convenient for basic tasks (and requires no extra install), but can be limited and slower on huge files.

lxml gives you the best of both: a friendly API and C-level performance. It’s no surprise that other tools (like Scrapy’s Parsel or even BeautifulSoup itself) often use lxml behind the scenes.

Installing lxml and your first parse

Before diving into the code, let's install lxml and run a simple parse to make sure everything is working.

How to install lxml

Installing lxml is straightforward. The easiest method is using pip in your command-line interface:

pip install lxml

This command will download and install the Python lxml library from PyPI. On most systems, this just works. If you have both Python 2 and 3, you might use pip3 install lxml to target Python 3.

Platform notes

- Windows

Pip will usually grab a pre-compiled lxml wheel for your Python version, so you don’t need a compiler or anything extra. Just make sure your pip is up to date. If you run into issues, install the latest Microsoft Visual C++ Build Tools (for older versions) and try pip install --only-binary=lxml lxml to force a binary wheel.

- Linux

You may need development headers if pip has to compile lxml. For example, on Debian/Ubuntu, install libxml2-dev and libxslt-dev (and python3-dev) before running pip. Often, however, pip will find a prebuilt wheel for your platform.

- macOS

Installation via pip is usually smooth. If you encounter a compile error on a Mac (especially with newer M1/M2 chips), ensure you have Xcode Command Line Tools installed (xcode-select --install). You might also use Homebrew to brew install libxml2 libxslt if needed, but in most cases pip install lxml suffices.

Another option is Conda (conda install lxml), which can be handy if you're using Anaconda/Miniconda. Conda will handle the C library dependencies for you.

After installation, you can verify it by opening a Python REPL and importing lxml:

>>> import lxml

>>> from lxml import etree

>>> print(lxml.__version__)

4.9.3 # (Your version may differ)

If no errors occur and a version prints, you’re ready to go!

First parsing example

Let's jump into a simple example to see lxml in action. We’ll parse a small XML string and inspect its content. This will introduce the core parsing interface of lxml: the etree module (ElementTree API).

from lxml import etree # import the etree submodule

# Define a simple XML string

xml_data = "<root><child>Hello</child></root>"

# Parse the XML string into an Element

root_element = etree.fromstring(xml_data

# Access data from the parsed XML

print(root_element.tag) # prints "root"

print(root_element[0].tag) # prints "child"

print(root_element[0].text) # prints "Hello"

Let's break down what's happening here:

- We used lxml import etree to get the etree module, which provides XML parsing capabilities.

- etree.fromstring(xml_data) parses the XML string and returns the root element of the XML tree (an <Element> object). This is a quick way to parse an XML snippet in memory. The variable root_element now represents the <root> element.

- We can treat root_element like a container of sub-elements. root_element[0] gives the first child element (the <child> element). We then printed its tag name and text content.

- The output shows the root tag "root", the child tag "child", and the text "Hello" which was inside the child element.

Under the hood, lxml built a tree structure from the XML string. The fromstring function is convenient for strings, while for files or larger documents, we might use etree.parse(), and we’ll see that soon. For now, we have lxml successfully reading XML

Creating and parsing XML/HTML with lxml

Now that we have lxml installed and have seen a basic parse, let's explore how to create XML structures from scratch and how to parse both XML and HTML content from strings or files. The lxml library excels at both building XML trees and parsing existing data.

Creating XML trees

One of the powerful features of lxml is its ability to create or modify XML/HTML trees intuitively. You can programmatically build an XML document using the Element classes, which is great for tasks like generating XML configuration files or preparing HTML programmatically.

To build XML, you typically use etree.Element to create nodes and etree.SubElement to append child nodes. You can also set text and attributes on elements. Let's create a simple XML tree:

from lxml import etree

# Create a root element

root = etree.Element("books")

# Create a child element with a tag and add text to it

book1 = etree.SubElement(root, "book")

book1.text = "Clean Code"

# You can add attributes to elements (e.g., an id)

book1.set("id", "101")

# Add another book entry

book2 = etree.SubElement(root, "book")

book2.text = "Introduction to Algorithms"

book2.set("id", "102")

# Convert the XML tree to a string and print

xml_str = etree.tostring(root, pretty_print=True, encoding='unicode')

print(xml_str)

This code produces an XML structure like:

<books>

<book id="101">Clean Code</book>

<book id="102">Introduction to Algorithms</book>

</books>

Here's what we did:

- Created a root <books> element. (Think of this like <books></books> in XML.)

- Added two <book> child elements inside the root, using etree.SubElement. We set the text of each book element to the book’s title.

- We also added an id attribute to each <book> by using the .set(name, value) method, which adds an attribute key-value pair to the element.

- Finally, we used etree.tostring to serialize the XML tree back to a string (with pretty_print=True to format it nicely). This is useful for viewing the output or saving it to an XML file.

A quick note on element properties: Every element has a .text attribute for text within the element, and a .tail attribute for text after the element (in case there’s text between sibling tags). In our example, we only used .text. Also, an element’s attributes are accessible via a dict-like .attrib property or methods like .set and .get.

For instance, book1.attrib would be {'id': '101'} in our code. These three properties - .text, .tail, and .attrib - cover all textual and attribute content of an element.

Parsing from strings and files

lxml can parse content from various sources, including in-memory strings, local files, and even web content. We already used etree.fromstring for an in-memory string. For an XML file on disk, we would use etree.parse. For HTML content, we have a couple of options as well.

Parsing XML from files

Suppose you have an example.xml file. You can parse it like this:

tree = etree.parse("example.xml")

root = tree.getroot()

The parse function reads the file and returns an ElementTree object. We then get the root <Element> via getroot(). One thing to note is that etree.parse returns a tree object (think of it as the whole document), whereas etree.fromstring returned a single root element.

In practice, you often won’t notice much difference, but it explains why parse(...).getroot() is needed to get the element.

Parsing HTML content

HTML is not always well-formed XML. Tags might not be closed properly, etc. lxml provides the lxml.html module (accessible via lxml import HTML) to handle HTML. There are two common ways:

- Use lxml.html:

from lxml import html

doc = html.fromstring(html_string_or_bytes)

This will parse an HTML string (or bytes from a webpage) and return an Element representing the root of the HTML document (likely an <html> element). It's designed to cope with common HTML quirks.

- Use etree.HTML: lxml’s etree has a convenience function for HTML:

doc = etree.HTML("<p>Hello</p>")

This will create an HTML tree. For example, etree.HTML("<p>Hello</p>") actually produces a full structure with <html><body><p>Hello</p></body></html>. lxml automatically wraps the snippet in the necessary <html><body> tags since we gave it a fragment.

Both methods above achieve similar results. Under the hood, they use the same parser tuned for HTML. The key point is that lxml’s HTML parser is forgiving - it can take HTML and XML mixed content or broken HTML and still build a tree. In fact, lxml's HTML support is robust enough to handle real-world, poorly formatted HTML in many cases.

Choosing XML vs HTML parse

If you know you have well-formed XML (e.g., an RSS feed or an XML config file), use etree.fromstring or etree.parse with an XML parser. If you're dealing with a webpage or snippet of HTML (which might not be perfectly well-formed), use lxml.html.fromstring or etree.HTML. The lxml library will use the appropriate parsing rules for each.

Additionally, lxml allows you to specify parser options. For example, you can create an etree.XMLParser or etree.HTMLParser with options like recovering from errors, removing blank text, and so on. However, for most cases, the defaults are fine.

Using XPath and CSS selectors in lxml

Once you have parsed an HTML or XML document into an lxml tree, the next step is usually to extract data from it. lxml supports two powerful methods for searching and filtering elements: XPath and CSS selectors. Many developers find XPath very powerful, while others prefer the familiarity of CSS-style selectors. Let's explore both.

XPath queries

XPath is a query language specifically designed for navigating XML/HTML tree structures. lxml’s support for XPath is excellent, as you can call the .xpath() method on any element (often the root) and pass an XPath string. The result will be a list of matching elements or values.

Basics of XPath

- / selects from the root node while // selects from the current node at any depth (descendants).

- Use tag names to pick elements (e.g., //div finds all <div> tags).

- You can filter by attributes using [@attr="value"]. For example, //a[@href="home.html"] finds <a> tags with a specific href.

- Use text() to get text nodes, and @attr to get an attribute’s value.

- Indices can select specific occurrences (e.g., (//p)[1] for the first <p>).

- You can also use conditions like //span[contains(@class, "price")] to match partial class names, etc.

Example XPath usage

Suppose we have an HTML document in lxml (perhaps parsed via lxml import HTML as doc). We want to get all the link URLs in a <nav> section and the text of those links. We could do:

# Get all link URLs in the nav

links = doc.xpath('//nav//a/@href')

# Get all link texts in the nav

link_texts = doc.xpath('//nav//a/text()')

Here’s what we did:

- //nav//a/@href means: find all <a> tags under any <nav> (any depth), and return their href attributes. lxml will return a list of href strings.

- //nav//a/text() means: return the text content of each <a> in the <nav>.

XPath can get very sophisticated (with functions, axes, etc.), but the above demonstrates common use. Because lxml uses libxml2 under the hood, it supports xpath expressions fully (XPath 1.0 standard), which is more than Python’s built-in can do.

Selecting nodes vs values

Notice that when we used @href or text(), we got strings. If we omit those and just do doc.xpath('//nav//a'), we would get a list of Element objects (each <a> Element). We could then further query each element or get its .text or attributes via .get('href').

Example: conditional XPath and hierarchy

Let's say we have an XML of books and we want the titles of books that cost less than 20. An XPath could be //book[price<20]/title/text(). Or if the price is an attribute: //book[@price<20]/title/text(). This shows how we can put conditions in square brackets to filter nodes.

XPath is extremely powerful for parsing HTML and XML because it lets you navigate by structure and conditions, not just by tag name. It might have a learning curve, but it can retrieve exactly what you need in one expression.

lxml web scraping tutorial

Now for the fun part: a mini web scraping tutorial using lxml. Let's go through the steps to retrieve a web page and extract data from it. For this example, we’ll use the requests library to fetch a page, and lxml to parse and extract information.

Remember to always scrape responsibly and within legal/ethical guidelines. If you’re scraping multiple pages, using reliable residential proxies can help prevent getting blocked by websites.

Let’s say we want to scrape a list of book titles and prices from an example site (we'll use the open website Books to Scrape for demonstration).

Step 1: fetch the webpage HTML

Use the requests library (or any HTTP client) to download the page content.

import requests

url = "http://books.toscrape.com/"

response = requests.get(url)

html_content = response.content # raw HTML bytes

We now have the page’s HTML in html_content. Using .content gives bytes; you could also use response.text for a Unicode string, but bytes are fine for lxml.

Step 2: parse the HTML with lxml

Next, we parse this HTML content into an lxml tree.

from lxml import html

doc = html.fromstring(html_content)

Here, we're using lxml import HTML via from lxml import html and then html.fromstring(...) to get a parsed document. The variable doc is now the root of the HTML DOM (likely an <html> element).

Step 3: extract the data with XPath or CSS selectors

Now the goal is to get all book titles and their prices from the page. If you inspect the Books to Scrape page HTML (you can do this in a browser DevTools), you'll find that each book is in an <article class="product_pod"> element. Inside each article, the title is in an <h3> tag (within an anchor tag), and the price is in a <p class="price_color"> tag.

Let's use XPath for this extraction:

# Extract all book articles

book_elements = doc.xpath('//article[@class="product_pod"]')

books = []

for book in book_elements:

title = book.xpath('.//h3/a/text()')[0] # text of the <a> inside <h3>

price = book.xpath('.//p[@class="price_color"]/text()')[0] # price text

books.append({"title": title, "price": price})

Here’s a breakdown of this code:

- doc.xpath('//article[@class="product_pod"]') finds all <article> elements with class "product_pod". We store these elements in book_elements. We use // to search through the whole document, and the [@class="product_pod"] is an attribute filter.

- We then loop through each book element. For each:

- We use a relative XPath (notice the . at the start of the string) to find the title text. .//h3/a/text() means "find an <a> under an <h3> under this book element, and get its text." We take the first result [0] since we expect one title.

- Similarly, .//p[@class="price_color"]/text() finds the price string.

- We append a dictionary with the title and price to our books list.

After this loop, the books list might look like:

[

{"title": "A Light in the Attic", "price": "£51.77"},

{"title": "Tipping the Velvet", "price": "£53.74"},

...

]

This is our extracted data! We successfully scraped the book titles and prices from the page using lxml.

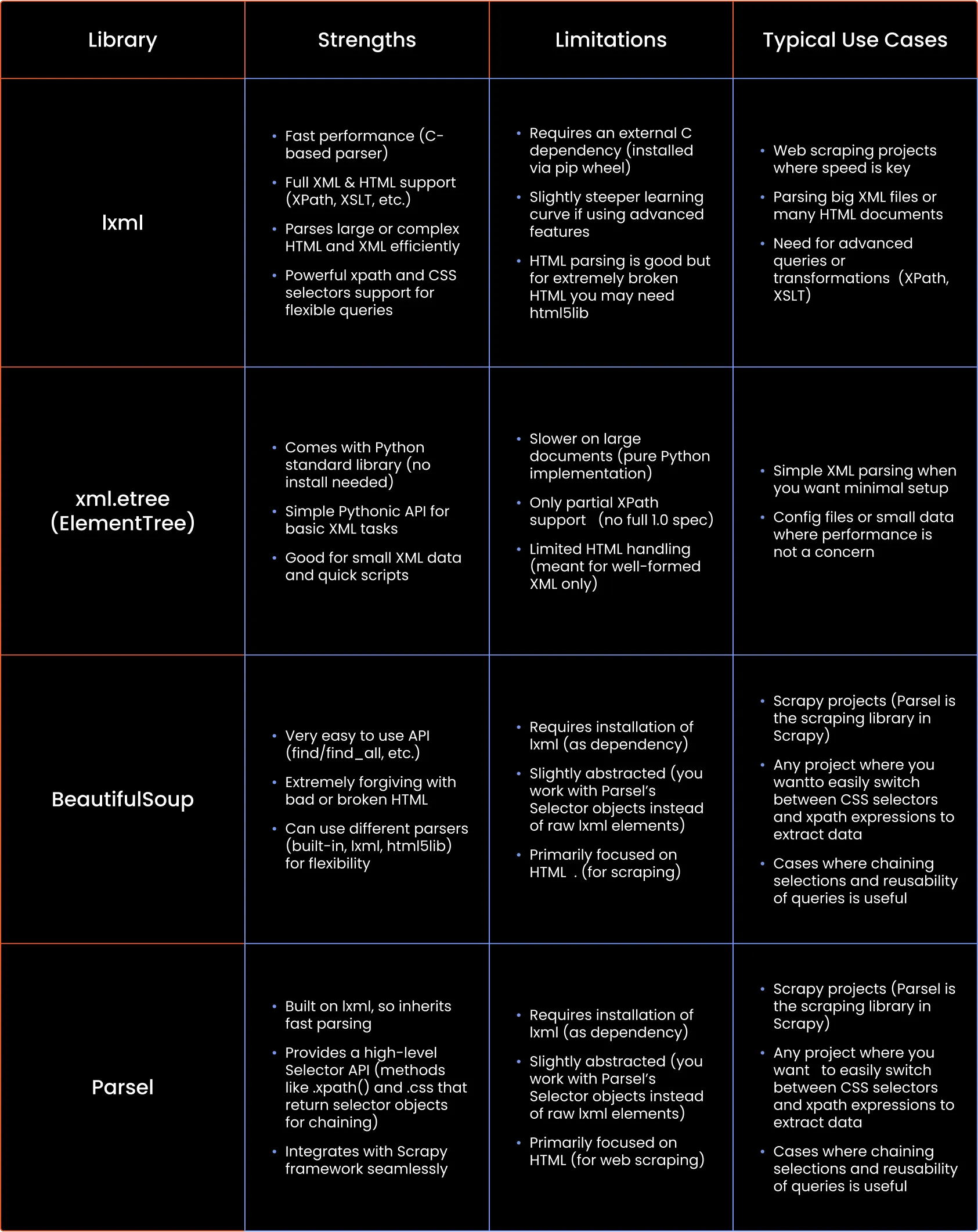

Comparison with other libraries

Python has several libraries for HTML/XML parsing and web scraping. How does lxml stack up against others like BeautifulSoup, the built-in xml.etree (ElementTree), or Scrapy’s Parsel? Below is a quick comparison of their strengths, limitations, and best use cases:

In (relatively) short: lxml is a go-to for performance and features, BeautifulSoup for ease and tricky HTML, ElementTree for simple built-in needs, and Parsel for a convenient web scraping interface (especially with Scrapy). In fact, lxml is often under the hood of the others: BS4 can use lxml as a parser, and Parsel is essentially a wrapper around lxml.

The good news is you don’t have to “pick one forever” - you can mix these tools. For example, you might parse with lxml and then use BeautifulSoup for some cleanup, or use lxml in one project and BS4 in another, depending on requirements.

Summary and further resources

This lxml tutorial showed how to use the Python lxml library for web scraping, parsing HTML, and working with XML documents. You saw how to install lxml, build trees, and extract data using XP path and CSS selectors.

For more help, visit the official lxml docs and try out XPath cheat sheets or tools like Parsel and Scrapy. Don’t forget to check out our Discord community, where you can share knowledge and tips with other web scraping developers!

Can lxml parse broken HTML?

Yes, using lxml import HTML or etree.HTML(), lxml can handle malformed HTML

What’s the difference between .text, .tail, and .attrib?

.text is inside the element, .tail is text after the element, .attrib holds attributes as a dictionary.

Does lxml support XML namespaces?

Yes. Use namespaces in XPath and access tags with the {namespace} tag.

Is lxml compatible with Python 3.x?

Absolutely. lxml works with all modern Python 3 versions.

How is lxml different from xml.etree or BeautifulSoup?

lxml is faster and supports full XPath. ElementTree is basic; BeautifulSoup is easier but slower.